US military academies remain plagued by racism: Report

US military academies remain inundated by institutional racism despite minor gains since proclaiming anti-discrimination policies a decade ago to bring in more racially diverse students, a new report reveals.

Eight years after he graduated from the US Military Academy at West Point, African American Geoffrey Easterling “remains astonished by the Confederate history still memorialized on the storied academy's campus -- the six-foot-tall painting of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee in the library, the barracks dormitory named for Lee and the Lee Gate on Lee Road,” according to an AP report published Friday.

He remembers feeling "devastated" as a Black student at the Army academy, when a classmate pointed out the slave also depicted in the Lee painting. "How did the only Black person who got on a wall in this entire humongous school -- how is it a slave?" he recalls thinking as quoted in the report.

Easterling later traveled the country as a diversity admissions officer to recruit students from “underrepresented communities” to West Point and observed: "It was so hard to tell people like, 'Yeah, you can trust the military,' and then their kids Google and go 'Why is there a barracks named after Lee?'"

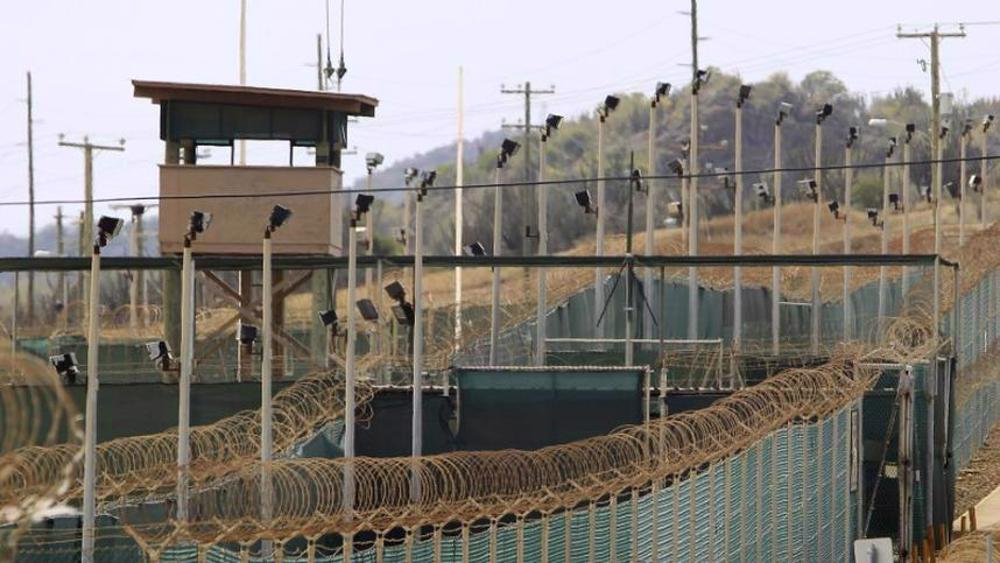

According to the report, American military academies provide “a key pipeline into the leadership of the armed services” and -- for the better part of the last decade -- they have welcomed more racially diverse students each year.

However, beyond blanket anti-discrimination policies, these federally funded institutions offer little details “about how they screen for extremist or hateful behavior, or address the racial slights that some graduates of color say they faced daily.”

Earlier in the year, AP published another report in which current and former enlistees and officers in nearly every branch of the armed services described a deep-rooted culture of racism and discrimination that stubbornly festers, despite repeated efforts to eradicate it.

Less attention has been paid to the premiere institutions that produce a significant portion of the services' officer corps -- the academies of the US Army, the US Navy, the US Air Force, the US Coast Guard and US Merchant Marine.

Some graduates of color from top US military schools who endured what they describe as a hostile environment “are left questioning the military maxim that all service members wearing the same uniform are equal,” according to the report.

That includes Carlton Shelley II, who was recruited to play football for West Point from his Sarasota, Florida, high school and entered the academy in 2009. On the field, he described the team as "a brotherhood," where his skin color didn't matter. But off the field, he said, he and other Black classmates too often were treated like the stereotype of the angry Black man.

Some students of color have spotlighted what they see as systemic discrimination at the academies by creating Instagram accounts -- "Black at West Point," "Black at USAFA" and "Black at USNA" -- to relate their personal experiences.

The latest annual defense spending bill mandated that the Defense Department survey all its military properties for references or symbols that potentially commemorate the Confederacy, including at West Point, which the commission overseeing the work picked as its first site to visit earlier this year. But the deadline to act on any recommendations is still more than two years away.

Following the murder of George Floyd in 2020, which sparked global protests, a group of West Point alums released a 40-page letter urging the academy to address "major failures" in combating intolerance and racism, adding "we hold fast to the hope that our Alma Mater will take the necessary steps to champion the values it espouses."

Shelley said the academy has significant work to do to retain and support students of color. In his class, he estimated about 35 Black students graduated -- "some crazy low number," he said. "And we started with a lot more."

The academies are a growing pathway to officer status for Black cadets, the report notes, citing 2019 data from the Under Secretary of Defense, with about 13 percent of Black active-duty officers commissioned through the five institutions, compared to 19 percent of white active-duty officers.

Most students who enroll -- nearly 60-70 percent -- are nominated by US senators or representatives from their home states as part of a system created in the 1840s to build a geographically diverse officer corps. Today, however, the country's changed demographics mean the system gives disproportionate influence to rural congressional districts that tend to be whiter.

Only six percent of nominations to the Army, Air Force and Naval academies made by the current members of Congress went to Black candidates, even though 15 percent of the population aged 18 to 24 is Black, according to a March report by the Connecticut Veterans' Legal Center. Eight percent of congressional nominations went to Hispanic students, though they make up 22 percent of young adults, the report said.

The diversity of nominations has improved slightly in the past 25 years, but the report noted that 49 Congress members did not nominate a single Black student while in office and 31 nominated no Hispanic candidates.

While the number of Hispanic cadets increased in the past two decades at the Coast Guard and Naval academies, Black cadets showed no noticeable increase during that time. In the class of 2000, there were 73 Black midshipmen in the Naval Academy and just 77 in 2020. At the Coast Guard Academy, there were 15 Black cadets in the 2001 class. And in 2021? Merely 16.

Two of the five academies -- West Point and the Air Force Academy -- now have their first Black leaders. But Easterling, the West Point graduate, noted that the faculty there remains mostly white, meaning students who "don't see themselves, and don't want to stay" can find it hard to ask for help.

Palestine Action wins again

VIDEO | Palestinian Authority's blockade of Jenin refugee camp reaches third week

Dec. 25: ‘Axis of Resistance’ operations against Israeli occupation

Lavrov warns West against challenging Russia's resolve to defend interests

VIDEO | Press TV's news headlines

Yemen parl. condemns ‘shameful’ silence of Arab states on Israeli crimes in Gaza, Syria

VIDEO | Iran’s Christians mark Christmas with hopes for Gaza resolution

VIDEO | Syrians take to streets nationwide against shrine desecration; HTS militants fire on protesters

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website