Kabul, Islamabad call for new era of relations

Pakistan and Afghanistan have called for a new era of relations as the chairman of Afghanistan’s High Council for National Reconciliation, Abdullah Abdullah, continues a tour of the neighboring country.

Speaking at an event in the Pakistani capital, Islamabad, on Tuesday, Abdullah emphasized his country’s appreciation of Pakistan’s help in the ongoing talks with the Taliban and the need for that new era.

“After many troubling years, we now need to go beyond the usual stale rhetoric and shadowy conspiracy theories that have held us back,” Abdullah said. “We cannot afford to pursue business as usual. We need fresh approaches and our people demand it of us.”

Abdullah, who also served until March as the Chief Executive in the National Unity Government led by President Ashraf Ghani, in the past had often accused Pakistan of supporting the Taliban and its allied militant groups operating across the troubled region.

On Tuesday, however, those accusations were not repeated, with Abdullah choosing instead to display his country’s commitment to not allowing its territory to be used against any other state.

“We do not want a terrorist footprint in our country or to allow any entity to pose a threat to any other nation.”

Striking a markedly conciliatory tone, Pakistani Foreign Minister Shah Mahmood Qureshi in a statement echoed Abdullah’s sentiment.

“[We need to have] recognition of the mistakes of the past,” said Qureshi.

“Unless we recognize that, how do we move forward? Let’s not shy away from reality. Let’s accept reality and add a new chapter to our bilateral relations and build a common future for ourselves.”

The bilateral relations have traditionally been mired in distrust.

The two neighbors accuse one another of doing too little to prevent the Taliban activities.

Over the past few years, dozens of people have been killed in a series of cross-border clashes between the armed forces of the two countries.

Kabul blames elements inside the Pakistani spy agency Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) for supporting the Taliban militants, while Islamabad blames the Afghan government for giving refuge to militants on its side of the border.

Pakistan was among the three countries that officially recognized the Taliban’s 1996-2001 regime, and Kabul has long accused Islamabad of continuing to covertly back the group.

Elsewhere in his remarks, Abdullah said the talks with the Taliban negotiators were ongoing after facing several hurdles at the outset.

“A new future, a peaceful future, is on the horizon,” he said. “As we are speaking here, delegations from both sides in Doha, they are sitting around a table, discussing the ways and means of ending decades of conflict through a political settlement in Afghanistan.”

Qureshi also repeated Pakistan’s stated position of not taking sides in the Afghan talks.

“We have no favorites,” he said. “My message is that we do not want to meddle in your internal affairs. My message is we respect and want to respect your sovereignty, your independence and your territorial integrity.”

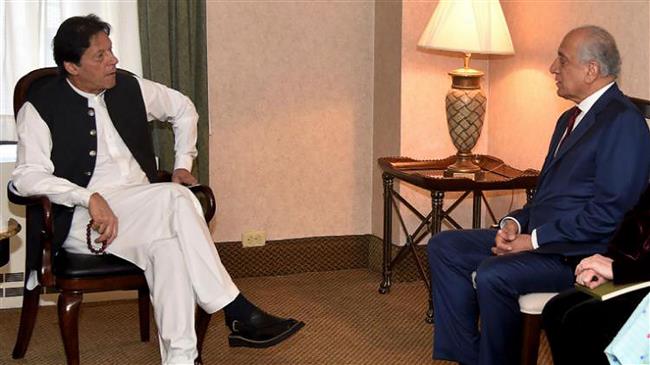

In an op-ed published in the Saturday issue of the Washington Post, Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan reiterated the need for the Afghan peace process to move forward but added that the pace would be slow.

Islamabad is thought to wield influence over the Taliban, though there is mistrust on the part of some within the militant group toward Pakistan. Pakistan has helped facilitate the talks between the Taliban and Washington in Qatar over the past year.

The negotiations are the result of a deal between the Taliban and the United States signed in February, which also paved the way for the withdrawal of all foreign forces by May next year.

Under the deal with Washington, the Taliban agreed to stop their attacks on US-led foreign forces in return for the US withdrawal of troops from Afghanistan and a prisoner swap with the government.

The Afghan government was a party neither to the negotiations nor to the deal, but it has been acting in accordance with its terms, including by agreeing to free the Taliban prisoners.

Official data shows that bombings and other assaults by the Taliban have surged by 70 percent since the militant group signed the February deal.

VIDEO | Sydney protests demand action as Israel faces ICC warrant for war crimes

Iran to host ‘important’ ECO foreign ministers' meeting in Mashhad

Wounded in Israeli strike, health of Kamal Adwan Hospital's director worsens

VIDEO | Press TV's News Headlines

Iran reports 11% drop in domestic red meat supply

Arab League affirms support for Iraq amid Israel's threats of military action

VIDEO | Fierce fight in Southern Lebanon

Over 1000 medics killed in Gaza as Israel systematically targets hospitals

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website