Sheikh Farid-ud-din Attar: Persian mystic and progenitor of fable in Iranian Sufism

By Humaira Ahad

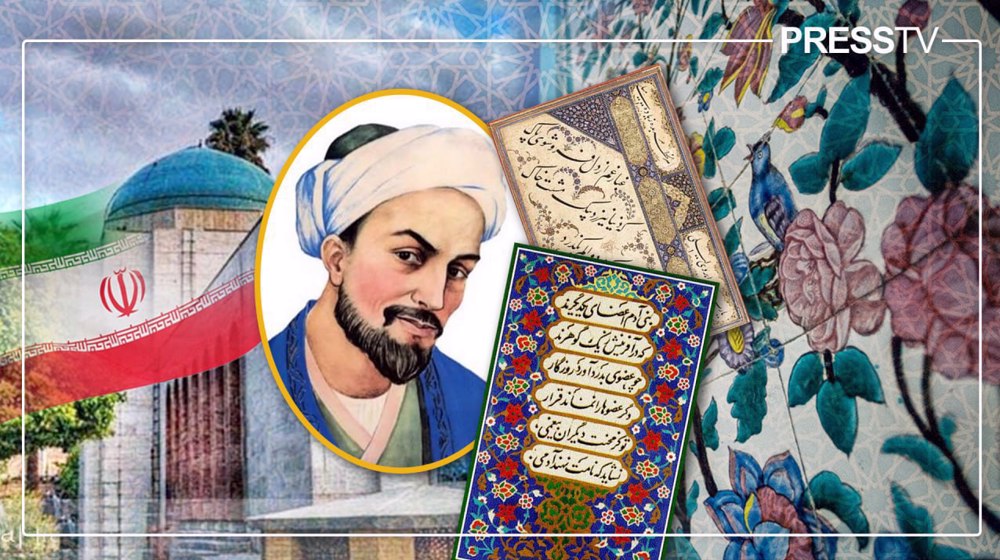

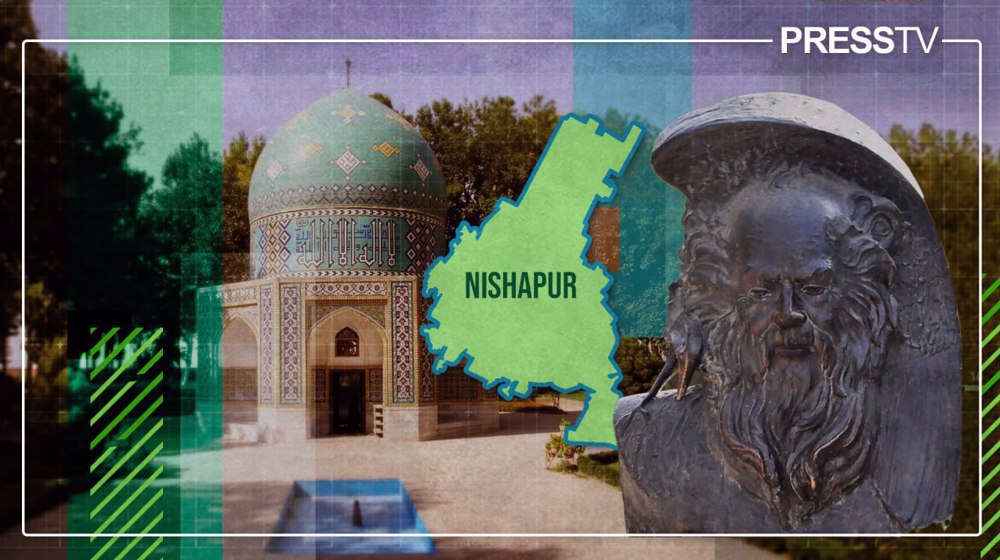

In a serene garden, nestled amid huge trees, the turquoise-coloured dome contrasts with the green around. This distinctiveness attracts visitors' attention, guiding them towards the mausoleum that has an element of tranquillity to it.

The Persian architecture of the building somehow mimics the philosophy of the great Sufi master, Faridud din Attar, who rests in the tomb at Neyshapur, a city in the northeastern Iranian province of Khorasan e Rezavi, close to the holy city of Mashhad.

The Persian mystic was born as Abu Ḥamed Moḥammad b. Abi Bakr Ebrahim in ca. 540/1145-46. He chose “Faridud din Attar” as his pen name.

He practiced his family profession of pharmacy and was quite famous among his patients.

“I feel a strange, indescribable calm at this place. Sitting in Attar’s garden is a dream come true. The frugal life this great master lived is mirrored in the peaceful aura that surrounds us here,” Sonia from France told the Press TV website while washing her prayer beads with water at Attar’s tomb.

Attar lived at a time when Mongols attacked Iran, killing millions of people throughout the province of Khorasan. He was killed by Mongols in April 1221 at the age of 78.

Margaret Smith, the British orientalist specializing in Sufism, narrates an interesting story related to Attar’s death.

According to Smith, when the Iranian Sufi master was taken captive by a Mongol, another Mongol offered a ransom of a thousand pieces of silver to save his life.

“His captor was on the verge of accepting, but Attar advised him that he was worth much more. Later, a third Mongol arrived offering a ransom of a sack of straw, whereupon Attar said, 'Take it, that's what I'm worth.' His captor, furious, beheaded him.”

Attar’s mystic works

Attar was proficient in literary sciences and techniques, theology and astronomy, interpretation of the Holy Qur’an and hadiths, medicine and botany, but he is known more today as a gnostic.

He is remembered as one of the most prolific Iranian poets, whose poems are laden with spiritual meanings that exude exceptional wisdom and insight.

There is a question of authenticity to the works attributed to Attar. However, in the introductions of the “Ḵhosrow-Nama”, Attar himself mentioned his other works, including “Asrar-nama”, “Manṭeq al-tayr”, “Moṣibat-nama”, “Elahi-nama”, “Jawaher-nama”, and “Sarḥ al-qalb”.

His famous work “Taḏkerat al-awlia” is missing from the list, probably because it is a prose work. Experts believe that its attribution to Aṭṭar can hardly be questioned.

Attar was the principal Muslim mystic poet of the second half of the twelfth century. Known for his radical theology of love, Attar’s poetry is still learned by heart and sung throughout Iran, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and the Indian subcontinent.

His masterpiece "Mantiq al-tayr”, or "The Conference of Birds", is considered to be the finest example of Sufi poetry in the Persian language after Rumi’s masterpiece Masnavi.

Mantiq al-tayr or The Conference of the Birds

The mythopoetic parable traces the journey of the world's birds in their search for King Simorgh, the legendary Lord of Creation.

The birds symbolize seekers on their journey to self-realization. Psycho-spiritual studies of the work suggest that the travel of the birds explains three significant concepts of psycho-spiritual value: the unrealized self, the process of self-realization, and the realized self.

In “Mantiq-al-tayr”, each bird represents a human fault that prevents humankind from attaining enlightenment.

The main message of the parable is the attainment of unification or tawhid as propagated by Islam.

The spiritual journey undertaken by birds gives a peep into Attar's profound, multi-dimensional view of existence.

At the end of the journey, the birds meet Simorgh, and they simultaneously experience themselves as many (Si-morgh, 30 birds) and also as one (Simorgh). Attar regards this as a complete transformation and unification.

Tadhkirat-ul-Awliya

The book is a collection of the lives of Muslim saints and mystics. It is Attar's only known prose work. It begins with Imam Jaʿfar al-Ṣadeq (AS), Oways Qarani, and Ḥasan Baṣri, and ends with Ḥallaj,

The compelling account of the execution of the mystic Mansur al-Hallaj, who had uttered the words "I am the Truth" in a state of ecstatic contemplation, is considered the most well-known extract from the book.

Ilahinama

The book deals with the concept of self-realization and the process of understanding God’s greatness. Attar says that when a person learns about his own physical and spiritual existence, he realizes the greatness of God’s great wisdom and incomparable power.

This book explains that self-knowledge is enlightenment leading to the knowledge of the wisdom of the universe and nature, as well as human and divine mysteries.

A mystic poet who influenced Rumi and Hafiz

Experts say that after Attar’s death, most of the poets in the Persian language were influenced by his style of writing.

Among the vast troupe of his followers, Moulana Jalal al-Din Rumi (d. 1273) and Hafiz Shirazi (d. c.1389) stand out.

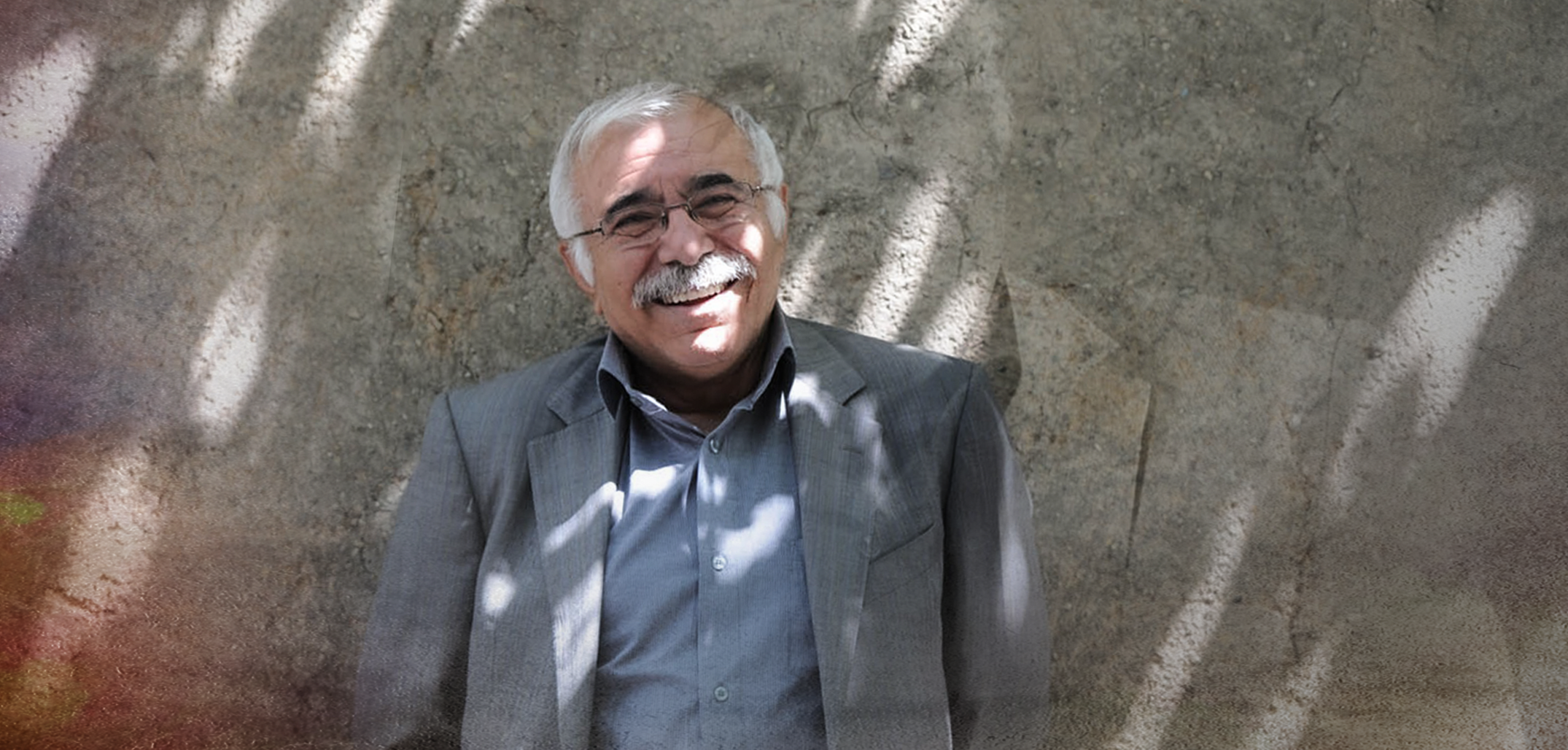

“Rumi’s verse is steeped more deeply in the fragrance of Attar’s poetry. His Mathnawi, which is the natural continuation of the mathnawiof Attar, represents the high point of all the previous Persian Sufi epics that began with the ‘Hadiqat al-Haqiqa’ of Sana’i, and was then expanded and elaborated upon in ‘Attar’s ‘Mantiq al-tayr’ and other mathnawis,” says Hossein Mohyeddin Elahi Ghomshei, an Iranian philosopher and a well-known author on mysticism.

Attar travelled through all the seven cities of love

While I am only at the bend of the first alley.

-- Maulana Rumi

Attar is regarded as ‘the Spirit’ since his poetry resulted in the grand spiritual revival of the Persian Sufi tradition.

“His verse was like the breath of the Messiah, resurrecting the dead stranded in the veil of passion, quickening them, giving them new life, guiding,” Ghomshei says in Attar and the Persian Sufi Tradition- Art of Spiritual Flight.

Comparing the two poets, the literary continuity becomes evident as Rumi creatively adopts many stories and mystical allegories from Attar’s works.

Wherever Rumi mentions Attar, he does it always with the utmost veneration.

Rumi is my name,

from whence I’m known as The ‘Prince of Rum’,

Although from all my verses a luscious sweetness pours –

In rhetoric and belles letters to ‘Attar I’m a slave.’

-- Maulana Rumi

Mystic experts are of the opinion that Iran’s national poet Hafiz was also intensely inspired by Attar.

“One could even say that in the entire Diwan of Hafiz, hardly a single ghazal can be found in which the spiritual presence and passionate fervour of Attar cannot be vividly felt,” Ghomshei writes about Attar’s impact on Hafiz.

Many Sufi scholars think that Hafiz had imbibed Attar's “melancholic romantic passion and the wildly unconventional temperament of the mystical non-conformist or qalander.”

Ghomshei hastens to add that no Sufi ever quotes the saying of another Sufi “unless his purpose is to illustrate his own inner contemplative experience” and describe his personal mystical state.

Meanwhile, at Attar’s grave, Sonia recites verses from “Mantiq-al-Tayr”, her eyes brimming with tears.

Remembering Sheikh Bahai, Iran's iconic theologian, astronomer, engineering genius

Remembering Saadi Shirazi, Persian poet whose message of universality endures

Tehran seeks UNESCO recognition for Iran mirrorwork art and Falak-ol-Aflak fortress

VIDEO | Press TV's news headlines

VIDEO | Pakistan’s business and cultural front unites for Gaza: Nationwide shutdown, boycott announced

US jets carry out more aggression against Yemen

Syrian militants enslaving Alawite women in Idlib governorate: Report

VIDEO | US pro-Palestinian campus protest

VIDEO | Palestinian civil defense rejects Israel’s probe and exposes the crime

India downgrades ties with Pakistan after deadly Kashmir attack

Iran’s steel output up 3.7% y/y to 3.3 million mt in March

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website