Why Molana Rumi and his works cannot be divorced from Islamic heritage

By Humaira Ahad

For the last three years, Iraj, Sara, Shabnum, and Yasaman have found a new passion – attending lectures on Molana Rumi’s Masnavi at a private center in the Iranian capital Tehran.

Thousands of miles away in New York, Mehdi is studying the Masnavi in Persian. He got the book from the Iranian holy city of Mashhad during his recent trip to Iran.

“This gives me insight into the subtle realities of life. During my PhD journey, Rumi has been a great help. I think I was in an abyss of darkness before knowing him,” Mehdi tells his teacher.

In the summer capital of Indian-administered Kashmir, Sabeeha, Irfan, Ali, Rahil, and Imran meet every Sunday at a book café in Srinagar to discuss Rumi’s poetry.

In London, Aarifa recently discovered an online English course on the Masnavi. A professor from Iran is teaching the course to her and many others.

“This is exactly what I need, you came as an answer to my prayers,” Aarifa tells her friend Shireen, who introduced her to the course.

Millions of copies of Molana Rumi’s poetry have been sold in recent years, making him the most celebrated non-Western poet in the West.

Quotes attributed to Molana Rumi have been circulated widely on social media platforms, with netizens affirming that the words provide motivation and hope amid gloom and doom all around.

Who is Molana Rumi?

Jalaluddin Mohammad Rumi came from a prominent family of Islamic scholars. He was born in 1207 A.D. in Balkh, a city in modern-day Afghanistan situated on the plain between the Hindu Kush Mountains and Amu Darya with around 2,500 years long history.

At the time of Molana Rumi’s birth, the Persian Empire spanned from Pakistan in the east to Greece in the west.

At the age of 33, Molana gained prominence as an Islamic scholar. He had some 10,000 followers at the peak of his teaching career, says his son, Sultan Walad, in his Diwan.

The transformative moment in Molana Rumi’s life came at the age of 37 when he met a wandering Persian mystic and poet, Shams Tabrizi.

“After years of unsuccessfully seeking a congenial soul, he at last met Rumi, whom he found to be his own potential soul,” Islamic scholar and psychologist Reza Arsteh wrote about Shams in his famous book, Rumi, the Persian, the Sufi.

After three years, Shams suddenly disappeared from Molana Rumi’s life. Experts on the Persian mystic say that Molana Rumi dealt with the pain of separation from him by writing poetry.

The West recognizes Molana Rumi as a mystic, spiritual master, and Sufi but rarely mentions the legendary mystic-poet’s Islamic background.

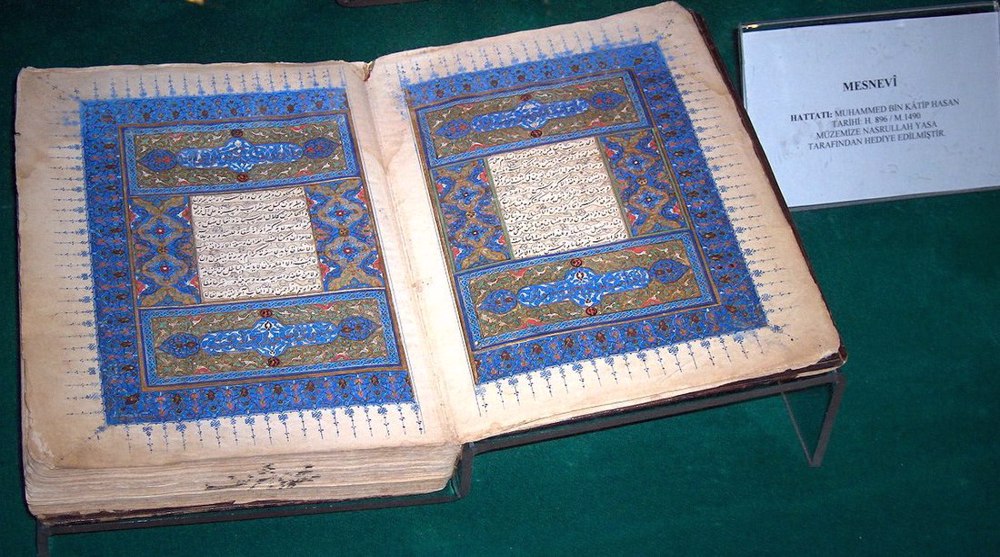

Rumi experts say that he practiced Sufism to draw closer to God. His 50,000-line magnum opus, the Masnavi, illustrates his deep yearning for nearness to the Divine.

“The Masnavi is a commentary upon these mystical states and stations. It places them within the overall context of Islamic and Sufi teachings and practices,” writes Islamic scholar and translator William Chittick in his book, The Sufi Path of Love.

“And it corrects the mistaken impression that one might receive by studying different poems in the Diwan in isolation and separating them from the wider context of Sufism and Islam.”

Rumi and Quran

Molana Rumi’s works are filled with citations from the Holy Quran. He uses Quranic stories and characters in his Masnavi that reflect his deep interest in Islam as a religion and a way of life.

“The story of Prophet Moses is mentioned in the Qur'an. Rumi uses Prophet Moses not once or twice but several times in the entire Masnavi. The story of Hazrat Adam in the Masnavi is copied from the Quran,” Ghodratollah Taheri, professor of Persian language and literature at Shaheed Beheshti University, told the Press TV website.

According to Rumi experts, the love motif that appears in Molana Rumi’s poetry is also inspired by the Holy Quran.

“In the Quran, God talks about love, the love for His creation. Contrary to what people think, the Quranic relation between God and His creation is based on love and not fear. Mewlana is well aware of God’s love and communicates it through his works,” Taheri adds.

Dr. Sayyed Amir Akrami, assistant professor at the Iranian Institute for Humanities and Cultural Studies, told the Press TV website that the Masnavi cannot be separated from the Quran.

“According to the interpretation attributed to Sheikh Baha'i, a great Islamic scholar, poet, and philosopher, the Masnavi is the Qur'an in the Persian language.”

Dr. Akrami said that the analogy used by Sheikh Baha'i reaffirms the close link between the Quran and the Masnavi.

“Molana even goes to the extent of saying that he is just acting as the narrator of the Masnavi and is not its creator. This great Persian mystic believes that the verses are just like the Quran if the mediator is removed. Revealed to the mind, heart, or soul of the narrator,” he said.

An internet search shows that around 6,000 verses of the Masnavi have Quranic references or are inspired by Quranic teachings.

Dr. Akrami said that this number equals around one-fourth of the Masnavi.

“This book is imbued with Quranic verses and Quranic ideas, and any attempt to sever the Masnavi from the Quran or the basic teachings of the Quran is simply a childish, futile attempt,” explained Dr. Akrami, who also teaches courses on the Masnavi and Diwan-e-Shams.

“Whosoever reads the Masnavi will understand that this book is nothing except a mirror image of the Quran.”

Molana Rumi’s other major work, Diwan-e-Shams, containing 2,500 odes to his master Shams Tabrizi, is also loaded with references to the Quran and the Holy Prophet (PBUH).

“As far as Diwan-e-Shams is concerned, if we look at Ghazal number 1948 (the website Ganjoor’s numerical order), the whole Ghazal is drawn from the Quran. Each verse ends with words from the Quran,” Dr. Akrami stated.

Rumi and West

As Molana Rumi became a household name in the West, his works received significant recognition in popular Western culture.

However, many English translations divorced his poetry from his belief in God and Islam, reducing the verses to love poems.

“After starting Persian poetics, I informed my followers that most Rumi pages post poorly translated content or outright false Rumi quotes. Eventually, this grew from Instagram stories and posts to a viral Twitter thread and now a full website,” a Rumi scholar Mohammad Ali Mojaradi said in a conversation with the Press TV website.

“The extent of this falsification, as well as the seeming total unawareness, was shocking to me.”

Mojaradi is known on social media as Sharghzadeh. He is a US-based researcher and translator who has studied Rumi’s works for years.

Mojaradi said he “seeks to rectify inaccurately translated and wrongfully attributed work” relating to the 13th-century Persian poet.

While Molana Rumi’s background as a Muslim closely shapes his work, this crucial link often gets ignored by the new-age translators.

Many interpreters who claim to know Molana Rumi have never studied the Persian language and are largely unaware of the Persian poet’s Islamic background and environment.

“I am lazy, as a matter of fact—it was hopeless to try to learn Farsi,” Coleman Barks, the American translator who is credited with expanding Rumi’s readership in the West, was quoted as saying in various media outlets.

Translations by other translators who claim to know Molana Rumi have little resemblance to the poet’s original works, often presenting distorted versions of his poetry.

Rumi experts regard it as a deliberate attempt to erase the centuries-old religious and spiritual history inherited and witnessed by Muslims throughout the world.

“There is a real bias against Islam and all things Eastern, and this has surely affected the Western version of Rumi, whether subtly or explicitly,” Mojarradi said when asked if erasing Rumi’s Islamic background can be linked to the Western bias against Islam and Eastern cultures.

Meanwhile, in Iran, Iraj, Sara, Shabnum, and Yasaman regard Rumi as an antidote to hate and suffering.

“In present times, we require Rumi more than ever,” they told the Press TV website.

Hope rekindled as rare Asiatic cheetah family spotted in central Iran

The 3rd Sobh International Media Festival extends entry deadline to March 5

UNESCO listing of Nablus soap testament to Palestinian craftsmanship, resilience

VIDEO | Wait... We're taking over Gaza?

VIDEO | Russia-US Alliance: Impact on the Middle East

VIDEO | PM Sánchez says Spain won’t allow forced displacement of Gazans

VIDEO | Press TV's news headlines

VIDEO | Israeli court sentences Palestinian child to 18 years in prison

US, France want mercenaries deployed in south Lebanon: Report

China condemns ‘unilateral and arbitrary’ US tariffs

IRGC commander: Third operation against Israel will be carried out

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website