British spy agency MI6’s key role in 1953 coup against Iran’s PM Mosaddeq

By Kit Klarenberg

This week marks the 60th anniversary of the military coup orchestrated by the CIA and MI6 that overthrew Iran’s then-Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddeq and his cabinet.

Working in tandem, British and American spies waged a devastatingly effective covert campaign using saboteurs, staged protests, false flag bombings, and assassinations, which ultimately put the reign of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi on a more brutal and dictatorial footing for the ensuing two and a half decades.

The coup’s history is fairly well-known - not least because the CIA has openly admitted responsibility for the mass violence and upheaval that unseated Mosaddeq on that fateful day, and many documents outlining its cloak-and-dagger activities during this period are in the public domain.

Yet, MI6’s central role remains largely unknown. Now, the sordid tale - or, what can be pieced together from an incomplete, thoroughly weeded archival record - must be told.

‘Stolen Property’

In May 1951, Iran’s parliament unanimously backed Mosaddeq’s proposal to nationalize the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC), and expropriate its assets.

The move was tremendously popular, instantly making the prime minister a national hero. Many believed that London’s dominance and exploitation of West Asia was finally over, and for the first time in centuries, people would take charge of their affairs, and profit from their country’s vast oil wealth.

It was precisely these hopes that meant from Britain’s perspective that Mosaddeq’s anti-imperial program could not be allowed to come to pass.

Through the AIOC, Iran’s resources were exploited, and the population was impoverished. Under a deal struck in 1901 and set to last until 1993, London garnered over 80 percent of the company’s profits.

Moreover, AIOC workers and their families toiled and lived in horrific conditions, while the firm’s British managers lived in staggering opulence, which wasn’t acceptable to the people of Iran.

London’s Joint Intelligence Committee remarked on the AIOC’s nationalization with typically dishonest restraint: “The situation in Persia has taken an unfortunate turn.”

In reality, irate British officials immediately began strategizing how to rid themselves of Mosaddeq and reverse the nationalization, before other countries in the region and beyond got similar ideas.

The first step was to impose sanctions banning Iran’s import of British commodities including steel and sugar, the freezing of Tehran’s accounts in London, and an embargo by the Royal Navy, under which any ship in the region suspected of transporting Iranian oil would be seized for carrying “stolen property”.

Direct military intervention was considered but eventually ruled out by then-Prime Minister Clement Attlee. Instead, it was decided to dislodge Mosaddeq via subversion and subterfuge.

The objective of British intelligence was to create a social and political climate in Iran conducive to violent revolution, in a manner that would keep London’s hand concealed in the event of insurrection.

This included secretly building a network of local opposition actors, who would agitate for Mosaddeq’s removal through a number of provocative if not outright incendiary methods, and deluging local and international media with black propaganda about the premier and his allies and supporters.

Some assets were recruited due to their personal and/or political dislike of Mosaddeq, and others - including local politicians and lawmakers - were bribed.

MI6 also paid newspaper editors and journalists to publish damaging stories about Mosaddeq. Historian Rory Cormac records how, in April 1952, US State Department officials privately commented with some interest on how almost the entire Iranian media had become hostile to the Prime Minister, apparently ignorant that this was London’s express doing.

Around this time, parliamentary elections were due to be held in Iran. Mosaddeq suspected that Britain intended to corrupt proceedings and destabilize the country, so postponed the election, then resigned.

London lobbied Shah Pahlavi to replace him with pro-British Ahmad Qavam. The plot failed when mass pro-Mosaddeq protests immediately erupted, and within a week the Prime Minister was reinstated.

A Foreign Office internal memo bitterly lamented: “The wheels of Islam need more lubricating than those of other faiths.”

Emboldened by victory, and having reached the end of his tether over nationalization, Mosaddeq broke off diplomatic relations with London outright, expelling its Embassy staff and all known MI6 officers operating his country.

Wounded, British intelligence scrapped its coup plans. Still, the regime change coast was far from clear in Tehran, as the Prime Minister - and the Iranian people he served - would soon find out.

‘Made in England’

Despite the unceremonious expulsion, MI6 continued to direct destabilizing actions in Iran through a secret communications network. This was hardly sufficient to precipitate Mosaddeq’s downfall though, so the British turned to their US counterparts, who could still operate in Tehran.

However, neither the CIA nor the White House or State Department was interested. At least initially.

At this time, Mosaddeq enjoyed cordial relations with officials in Washington, who viewed him as a useful ally in the fight against Communism. It is largely unknown today that in the autumn of 1951, he toured the country for six weeks, attempting to drum up political and public support.

In many speeches, he drew comparisons between the US struggle for independence from Britain and his oil nationalization ambitions. Typically, audiences - and the mainstream press - were highly receptive.

Fast forward a year though, and London’s determined efforts to batter down US support for Mosaddeq were beginning to bear fruit. In November 1952, an official from the British embassy in Washington formally recommended a coup to remove the Prime Minister, to the CIA and State Department.

The Americans were led to believe MI6 had a well-developed plan involving its own agents in Iran, which was certain of success. All they needed to do was give the green light.

The CIA was amenable, yet State balked, arguing there was scope for failure, and Western sponsorship to be exposed. Nonetheless, an influential seed had been planted, and when Dwight. D Eisenhower became President in January of the next year, an old friend of the British - in particular Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Foreign Minister Antony Eden - was safely ensconced in the Oval Office.

Offered a significant cut of AIOC’s profits in return for US backing, Eisenhower signed off on a joint CIA/MI6 plan to get Mosaddeq. From there on out, the two agencies worked overtime to at last create the revolution-ripe atmosphere in Tehran sought by the British two years earlier.

Once the pesky Prime Minister was finally ousted, Shah Pahlavi would reign supreme, and dutifully do the bidding of his patrons in London and Washington.

So, newspapers, radio broadcasts, and the walls of major cities were blitzed with anti-Mosaddeq propaganda, and also pro-Mosaddeq propaganda purporting to be the work of Communists, to paint the Prime Minister as a Red.

Religious leaders were attacked and mosques were bombed by CIA operatives posing as Mosaddeq sympathizers. Iranian government officials at every level were targeted for kidnap and murder.

Against this chaotic backdrop, seeds of chaos rapidly germinating, Pahlavi feared that the same forces would in time turn on him too. In May 1953, he told the US Ambassador to Iran Loy W. Henderson:

“The British threw out the Qajar dynasty; they brought in my father; they threw out my father; and they can throw me out or keep me as they see fit…If the British wish me to go, I should know immediately so that I can quietly leave. Do the British wish to substitute another Shah for me or to abolish the monarchy? Are the British [behind] present efforts to take away my powers and deprive me of my prestige in Iran and abroad?”

This prompted a private intervention from Churchill, who claimed that while the British “do not interfere in Persian politics, we should be very sorry to see the Shah lose his powers or leave his post or be driven out.”

Nonetheless, Pahlavi’s fears about London’s malign meddling stayed with him until his dying day.

‘Junior Partner’

The CIA and MI6-orchestrated and financed upheaval in Iran gathered in intensity as August 1953 approached, culminating in a four-day-long series of staged anti-government protests.

Attendees, who only numbered a few thousand, were overwhelmingly directed and funded by British and American spying agencies. All along, Shah Pahlavi issued calls for the Prime Minister to resign, which eventually provided a pretext for the military to storm government buildings, and seize power.

While suspicions of British and American involvement simmered, the world was for many decades convinced that Mosaddeq’s fall resulted from an organic expression of mass public dissatisfaction.

It was not until Iranian students seized the US embassy in Tehran in 1979, known as the ‘den of espionage’, seizing sensitive files and documents that hadn’t yet been burned, reality began to emerge.

So thrilled with the results were officials in London, they slammed MI6 for not pursuing the “regime change” project earlier, and more aggressively.

Their Iranian caper provided a compelling blueprint, through which their Empire could be maintained via covert means, as its military and financial might, and ability to overtly project force overseas were ever-dwindled. It was a model that could - and would - be repeated over again not only throughout West Asia, but the entire world, thereafter by British intelligence.

Meanwhile, the CIA was likewise energized by its clandestine performance, so commissioned an official internal review of the operation, not intended for public consumption.

Authored by career agency officer Donald Wilber, who led, planned and executed Langley’s contribution to Mosaddeq’s overthrow, he attributed the connivance’s success to the “active cooperation of the United Kingdom and their assets.”

It is uncertain whether this appraisal was shared with London at the time, but either way, this finding was gold dust to MI6.

Towards the end of World War II, a UK Foreign Office official remarked that soon, Britain would “be expected to take her place as a junior partner in an orbit of power predominantly under American aegis.”

Ever since London’s political and security apparatus has been overwhelmingly concerned with exploiting and manipulating that aegis for its own ends.

The Iranian coup showed British intelligence how to effectively steer the bigger, richer, more powerful US Empire in directions of its own choosing.

The 60 years have been an unending battle to repeat that success.

Kit Klarenberg is an investigative journalist exploring the role of intelligence services in shaping politics and perceptions.

Brewing storm: Which US bases in West Asia are within Iran’s missile crosshairs?

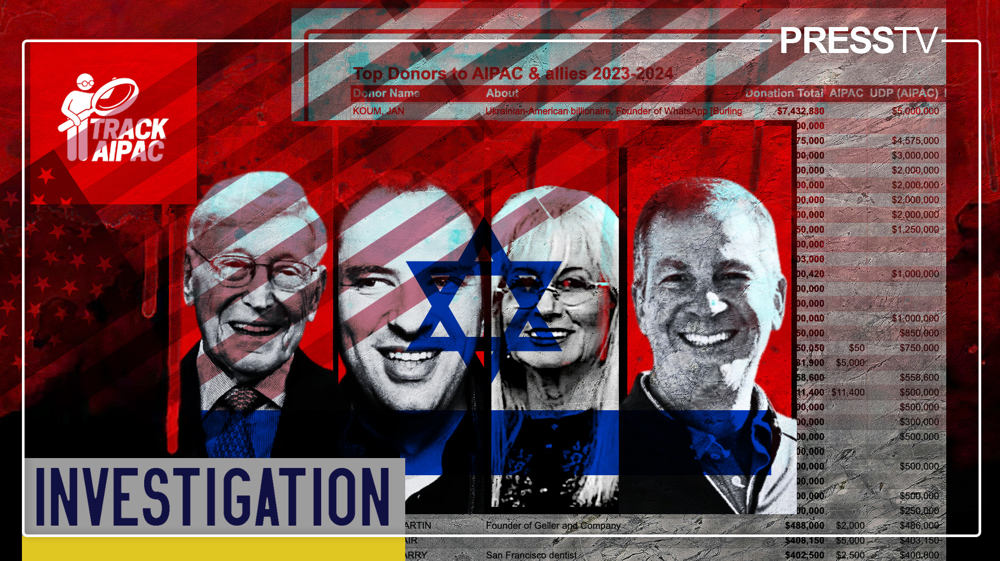

Bankrolling genocide: The biggest donors to AIPAC, leading US Zionist lobby group

Exposing Britain’s long-running overt and covert war on Yemen

Netanyahu says Qatar 'not an enemy state'

UN rights body demands Israel 'prevent genocide' in Gaza

VIDEO | Unceasing genocide vs. Palestinians

VIDEO | Iran's response to Trump's threat

US orders social media screening for student visa applicants to bar those critical of Israel

VIDEO | Iran marks anniversary of Israeli attack on embassy in Damascus

Hamas slams Ben-Gvir’s storming of al-Aqsa Mosque as ‘dangerous escalation’

Moving against global tide, Israel eliminates all tariffs on US goods

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website