Explainer: Who’s Aung San Suu Kyi and what’s her role in Rohingya genocide?

By Syed Zafar Mehdi

Myanmar’s ruling military junta on Tuesday announced partial clemency to the country’s former leader Aung San Suu Kyi, pardoning her in 5 out of 19 offenses, for which she was sentenced to 33 years in jail.

The five charges include offenses against defamation, natural disaster laws, export and import laws and the country’s telecommunication law, according to media reports.

The partial clemency, according to the Burmese state media, is part of the general amnesty granted by the junta to more than 7,000 prisoners in the South Asian country to mark a Buddhist festival.

The announcement came days after the Nobel laureate was reportedly transferred from prison to house arrest in the capital Naypyidaw more than two years after the military takeover of the country.

Suu Kyi, 78, has appealed against convictions for offenses including incitement, election fraud and corruption that were slapped on her following the February 2021 coup.

Who is Aung San Suu Kyi of Burma?

Suu Kyi is the daughter of Myanmar’s independence hero General Aung San, who spent years in detention between 1989 and 2010 for protesting against the country’s long-running military rule.

Her father was assassinated just before the multi-ethnic South Asian country won independence from British colonialism in 1948. She was barely two years old at the time.

Suu Kyi spent years in India, where her mother served as a diplomat, and studied at the Oxford University in the UK where she eventually settled with her British husband and two children.

In 1988, she returned to Myanmar in the middle of a political crisis that gripped the country. A later year, she was sent to prison for her political activities.

In 1991, she won the Nobel Peace Prize for her anti-military campaign and was eventually released from house arrest in 2010, five years before her National League for Democracy (NLD) swept to power.

Even though the Burmese Constitution forbade her from becoming the head of the state, as her children had foreign citizenship, she was the de-facto ruler as the ‘state counselor.’

Her Buddhist party returned to power in November 2020 but the country’s military junta disputed the election result, alleging large-scale fraud and irregularities.

In 2021, Suu Kyi was deposed by the powerful military that took full control of the country. She was arrested the day parliament was slated to hold its first session under the new government.

The coup triggered countrywide violence with more than 3,800 people getting killed in the crackdown, according to a local monitoring group, the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (AAPP).

What’s her involvement in Rohingya genocide?

After Suu Kyi took the reins of power in 2015 as the de-facto ruler, Myanmar plunged into a fresh crisis related to the persecution and genocide of minority Rohingya Muslims.

In 2017, hundreds of thousands of Rohingya Muslims fled Myanmar for neighboring Bangladesh and India to escape the unutterable horror in the form of persecution, murder, arson and rape.

The savagery of the Suu Kyi regime forces in the Muslim-dominated Rakhine state was described by the United Nations at the time as “a textbook example of ethnic cleansing.”

Soldiers took away infants from their mothers and set them ablaze while hate-mongering Buddhist mobs under the protection of regime forces burned down properties that belonged to Rohingyas, with some estimates putting the death toll at 6,700, including 730 children.

Myanmar faces a lawsuit that accuses it of genocide against the Rohingya community at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) while the International Criminal Court (ICC) is also probing the country for crimes against humanity. Suu Kyi was directly complicit in the genocide.

In December 2019, the then-Myanmar leader brazenly defended her military at the ICJ and dismissed the grave accusations of mass killings, rape and expulsion of Rohingya Muslims.

“The Gambia has placed an incomplete and misleading picture of the factual situation in Rakhine state,” Suu Kyi said at the UN court after Gambia accused Myanmar of violating the 1948 Genocide Convention.

“Surely under the circumstances, genocidal intent cannot be the only hypothesis,” she hastened to add while downplaying the anti-Rohingya crackdown in 2017 as “internal conflict.”

Was Suui Kyi biased against Muslims even before 2017?

Even before the genocide in 2017, reports suggest Suu Kyi harbored deep anti-Muslim animosity. She did nothing to stop the military-aided-and-abetted ethnic cleansing of Rohingya Muslims.

In a 2013 interview, the former Myanmar leader dismissed reports about violence against the minority Rohingya community, saying Buddhists in the Rakhine state were afraid of “global Muslim power.”

In 2017, in a phone call with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, Suu Kyi claimed there was a “huge iceberg of misinformation” about the Rohingya issue to benefit “terrorists.”

In August 2018, while reviewing her two years in power, she again defended her far-right government’s ethnic cleansing of Rohingya Muslims in the Rakhine state.

“We who are living through the transition in Myanmar view it differently than those who observe it from the outside and who will remain untouched by its outcome,” she said at the time.

“The danger of terrorist activities which was the initial cause of events leading to the humanitarian crisis in Rakhine remains real and present today.”

“Suu Kyi was often accused of harboring a possible (anti-Muslim) bias of her own, for she was an elite Bamar and thus a beneficiary of the ethnic hierarchy that had formed in Myanmar,” Francis Wade writes in his book ‘Myanmar’s Enemy Within: Buddhist Violence and the Making of a Muslim Other’.

Rohingya have no legal status in the Buddhist-majority Myanmar and are one of the world’s most persecuted communities with Buddhist extremists repeatedly calling for their extermination.

Current status of Rohingya refugees

This month marks the sixth anniversary of the brutal military crackdown against the community.

UN refugee agency has insisted that the repatriation of Rohingya to their home country must take place in “safe and dignified conditions that pave the way for lasting solutions.”

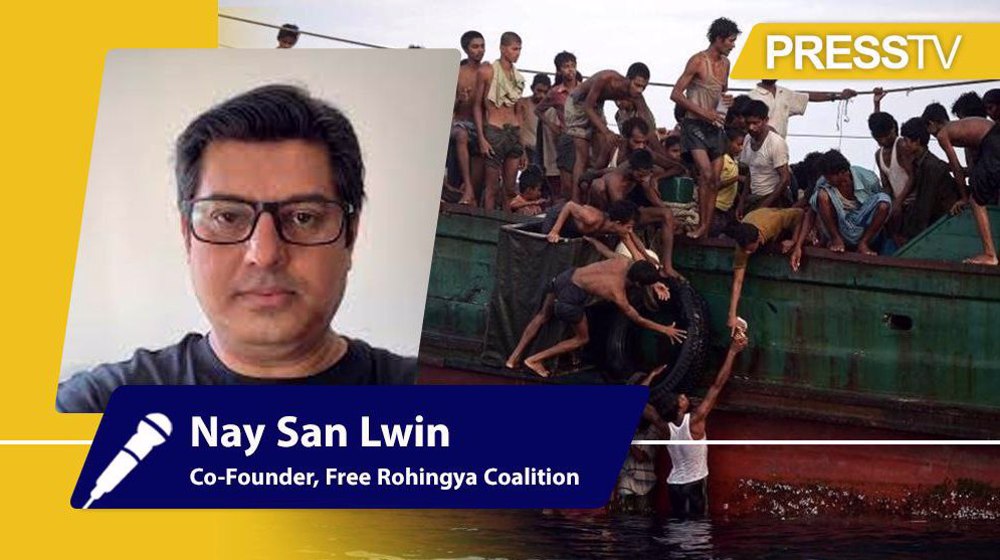

In a conversation with the Press TV website last month, Nay San Lwin, co-founder of Free Rohingya Coalition, faulted the ongoing repatriation process of Rohingya, calling it “a transfer from the refugee camps in Bangladesh to a concentration camp in Myanmar.”

“As I understand it, repatriation should involve refugees returning to their homeland, where they would regain their land, and rights, and receive reparation. However, the recent process doesn't seem like true repatriation. It feels more like transferring the refugees from one camp to another,” Lwin stated.

He hastened to add that 130,000 refugees inside the country have been stuck in camps for over 11 years, saying they are more like “prisoners” than “internally displaced persons (IDPs).

“They have very limited rights and depend on aid organizations for education, healthcare, and food. The Myanmar regime seems intent on destroying them, and keeping them in these camps only makes their lives worse,” the activist, who has even faced threats to his life, told the Press TV website.

“Rakhine State has become a killing field for the Rohingya. This process requires multiple parties to provide extensive assurances. Simply returning without any guarantees is akin to returning to a killing field.”

Trump’s immigration policy and unfair targeting of Hispanic communities

46 years since Islamic Revolution, Palestine still at the heart of Iran's foreign policy

‘Make America Mafia Again’: Gaza and Trump’s anti-intellectual imperialism

US special envoy in Kiev amid war of words between Trump, Zelensky

Hamas says ready to free all Israeli captives at once in phase two of truce

Israel kills one, injures two in southern Lebanon: Media

‘Colonial powers’ have no right to determine fate of Palestine: Qalibaf

Explainer: Why are MK-84 2,000-lb bombs approved by Trump for Israel so deadly?

President Pezeshkian: Iran, Qatar opening new avenues for cooperation

VIDEO | Displaced return home despite destruction

IRGC unveils new homegrown smart missiles, drones drill

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website