Nahel's murder tied to French state’s violence against Muslims, non-whites

By Xavier Villar

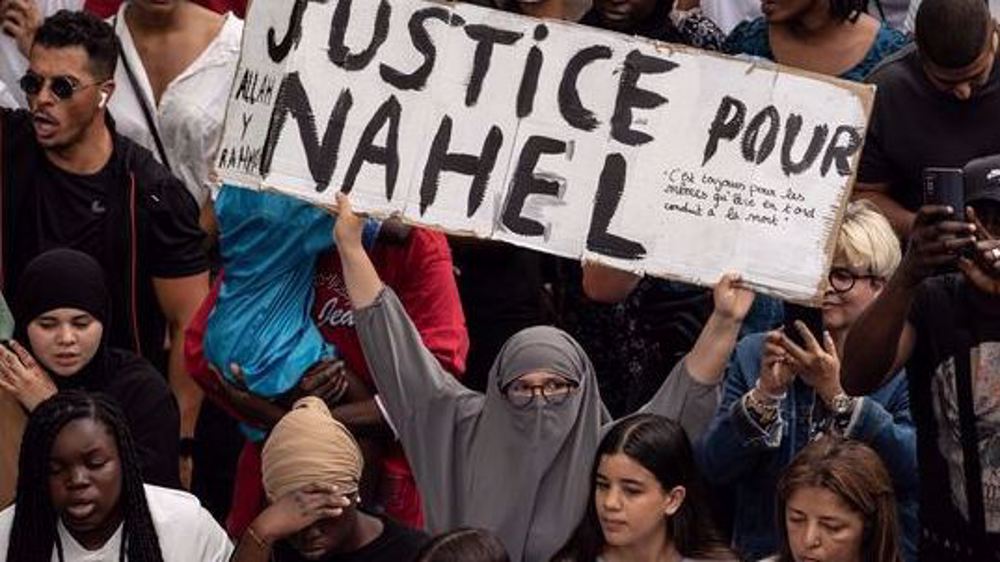

The brutal murder of 17-year-old Nahel M by the French police in the city of Nanterre, near Paris, has sparked a massive uprising against (post)-colonial violence by the French state.

It is safe to say that the postcolonial order is postcolonial not because colonialism has ended, but because the colonial-racial logic that privileged white supremacism is being questioned, and this challenge is provoking the white backlash.

The cold-blooded murder of Nahel, therefore, cannot be understood in isolation, rather it is necessary to connect it with the violence of the French state, particularly the violence directed towards Muslims and other non-white populations.

It is important to emphasize that the young boy came from an Algerian family, which in France, as well as throughout Europe, means that he was considered a primary target of state violence and its disciplinary powers.

French historian Emmanuel Blanchard argues that the colonial origins of the police institution in France and the Western world are undeniable. Blanchard highlights the genealogy of police work in slave plantations, where its main objective was to pursue escaped slaves.

Throughout the colonial period and subsequently, in the post-colonial era, we observe one of the fundamental functions of the police in the West is that of repression and control of bodies that deviate from the norm.

We can refer to them as colonized bodies, racialized bodies, or, as Egyptian anthropologist Talal Asad suggests, non-secular bodies.

In France, particularly, we can observe how high-ranking police and military officials were involved in both suppressing anti-colonial uprisings abroad and within the country itself.

For example, in 1945, Maurice Papon was appointed head of the Algerian sub-directorate in the French interior ministry. In 1958, he was transferred to Paris and tasked to combat "North African subversion."

Papon imported doctrines, methods, and agents that had been deployed in the colonial war in Algeria. Furthermore, he was responsible for the massacre of Algerian protesters that took place on October 17, 1961, following the repressive model used against popular demonstrations in Algeria.

This is not an isolated case. On a much broader scale, we observe how the US Department of State used the film "The Battle of Algiers," directed by Italian filmmaker Gillo Pontecorvo in 1966, as a learning resource for its senior military commanders to study the counterinsurgency tactics employed by the French.

The screening of the film took place shortly after the events of September 11 and was aimed at training the American troops who would later occupy Afghanistan.

However, as pointed out by Professor Sohail Daulatzai from the University of California-Irvine, this way of viewing the film consciously denies the racial logic present within it and the director's critique of colonial violence and exploitation.

"The Battle of Algiers" remains as relevant today as it was 50 years ago, as it skillfully captures the current global political condition. The international "war on terrorism" has generated racial panic towards the "Muslim other" and has given rise to significant ideological capital and anti-Muslim policies that are responsible for the murder of Nahel.

Another point to consider is that the film visually portrays how Algerians, including the protagonist Ali la Pointe, live in the crowded Casbah, surrounded by barbed wire, military checkpoints, watchtowers, and armed guards, while the European part of the city overflows with wealth, culture, and gardens.

In France, we find a similar urban and ontological division in the so-called banlieues, where Nahel lived, in contrast to other posh areas.

Banlieue is a widely used term that refers to an urbanized area on the outskirts of a large city. Literally, banlieue means "forbidden location." These urban areas are mostly inhabited by the non-secular bodies mentioned earlier.

The banlieues not only inherit the French colonial urbanism in Algeria but also reflect a political control derived from colonial white supremacism.

The banlieues, like non-secular bodies, exist in a state of permanent exception. These states are not a temporary or anomalous "exception" to the law, as proposed by Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben in his work.

On the contrary, these states of exception are constant on the other side of the ontological line of being. Even when these states of exception cease to be temporary, they continue to be permanent states of exception in an ontological sense and backed by the law.

For this reason, an exceptionalist interpretation of the state of exception is insufficient to understand how the lives of racialized individuals, especially Muslims, are subjected to various forms of violence in their daily lives.

The colonial war against the internal enemy, which is essential for creating and sustaining the French identity, is directed against those subjects who obstruct the closure of the nation.

In this sense, Muslims and their public presence mark the boundaries of the nation.

It is Islam, understood as a political identity and its global character, that threatens the particularistic and national project of France. That is why Macron's government has attempted to construct a "French Islam," disciplining Islam to fit within the framework of the state.

To achieve this goal, it is also crucial to discipline non-secular bodies, those that do not represent the nation or conform to the foundational fantasies of modernity, rationality, and agency.

The murder of Nahel at the hands of the French police is more than a personal tragedy. It is a reminder of how contemporary Western society is structured through a non-dialectical division that rigidly separates human beings from "the rest."

Xavier Villar is a Ph.D. in Islamic Studies and researcher who divides his time between Spain and Iran.

(The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect those of Press TV)

Iran-US nuclear talks: A historical overview and future expectations

How Bernie Sanders condemns genocide in Gaza without actually condemning it

Trump's proposed travel ban should bar US from hosting 2026 FIFA World Cup

VIDEO | Iran seeks foreign investment to boost oil, gas sectors

Iran condemns terror attack in India's Kashmir region

After second Signalgate scandal, Democrats call for Hegseth’s resignation

Mahmoud Khalil missed son's birth after US officials denied temporary release

Iran’s annual inflation up 0.7% to 33.2% in April: SCI

Ayatollah Sistani offers condolences on passing of Pope, hails his role in promoting peace

Iran says expert-level talks with US postponed to Saturday

Iran issues jail sentences, fines for foreign crews of fuel smuggling ships

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website