Afghanistan’s denial of Iran’s water rights destroying agriculture, wetlands

By Maryam Qarehgozlou

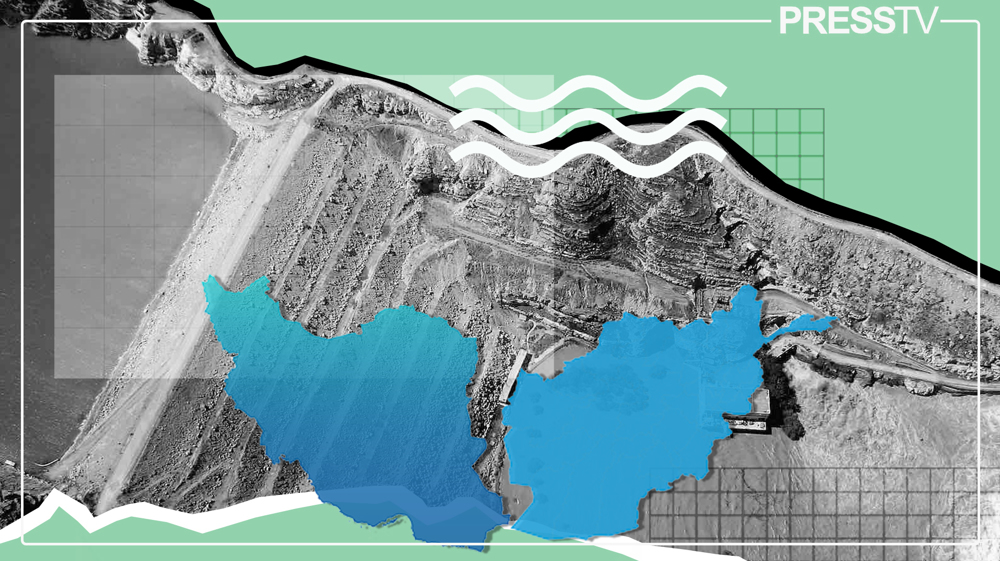

As the long-running water dispute between Iran and Afghanistan drags on, experts warn that it is taking a heavy toll on agriculture and water bodies, especially the wetlands in southwestern Iran.

The issue of Afghanistan’s lack of adherence to the 1973 water-sharing treaty and denying Iran its water rights under the pact has come back to center stage in recent months.

Top Iranian officials, including President Ebrahim Raeisi and Foreign Minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian, have in strongly-worded statements warned the de-facto Taliban government in Kabul to address the issue that has been a bone of contention between the two neighbors for a long time.

The dispute has often fueled political and diplomatic tensions between Tehran and Kabul, mainly because of the disastrous impact it has on water bodies and agriculture in Iran.

Speaking to the Press TV website, environmental experts said violation of Iran’s water rights from the Hirmand River, also known as the Helmand River, has hit agriculture and made the border region barren.

The two neighboring countries have been grappling with the issue of low rainfall for very long and the dispute over shared water resources has only made the situation worse, especially in Iran.

Behnam Andik, a Ph.D. Candidate in Water Resources and Environmental Engineering at the University of Tehran told the Press TV website that the harmful impact of water scarcity “knows no political borders.”

“Water scarcity has adversely affected both the Sistan region in Iran and Nimruz province in Afghanistan, and as a result, Hamoun International Wetlands are disappearing and agriculture is almost dead,” he remarked, painting a somber picture of the prevailing situation.

The case of Hirmand River

Hirmand River which emerges in the Hindu Kush Mountains in Afghanistan near the capital Kabul feeds the Hamoun, the transboundary wetlands on the Iran-Afghanistan border.

The Hamoun are made up of three lakes: Hamoun-e Helmand, located entirely in Iran, Hamoun-e Sabari on the border, and Hamoun-e Puzak, almost entirely inside Afghanistan.

The conflict over the rights to access the water in the Hirmand River dates back to the late 1800s. As Afghanistan failed to ratify a 1939 treaty on sharing the water, the two countries got embroiled in a bitter dispute that continued for another century.

In 1973, the two sides finally agreed on a twenty-six cubic meters per second water flow into Iran which equals 820 million cubic meters of water a year.

The treaty was ratified by the two countries in 1972, but not fully implemented due to political developments in the two countries, including the 1973 political coup in Afghanistan.

However, a bilateral agreement was signed by the two sides in 2003 to implement the treaty. Afghanistan, however, again failed to honor the treaty and denied Iran its water rights.

In an interview with Iran’s state broadcaster on Tuesday, the Iranian president’s special envoy for Afghanistan affairs, Hassan Kazemi Qomi, said the treaty is a “legal issue” to which the Afghan government is committed and must show its adherence in letter and spirit.

He said only 27 million cubic meters of water reached Iran last year instead of the 820 million cubic meters that the country should receive under the 1973 accord.

Currently, about 60,000 hectares of wetlands in the Hamoun region in Iran are protected under the Ramsar Convention, which is an intergovernmental treaty that provides the framework for the conservation and wise use of wetlands and their resources.

Environmental predicaments

Despite that, environmental predicaments coupled with Afghanistan’s dam-building projects have aggravated water shortages in Iran’s southeastern Sistan and Balouchestan province for decades, as it is not receiving its due share of water from the river.

Since 2001, Afghanistan has announced plans for the construction of at least 104 new dams, Andik said. The plans include building 35 dams on the Hirmand River which directly reduces Iran’s water supplies.

A short video published on the official Twitter account of the United Nations University Institute for Water, Environment and Health shows the drastic decline of water levels in the Chah-Nimeh Reservoirs in the Iranian part of the Helmand River Basin from 2016 to 2023.

Drastic decline of water levels in the Chah-Nimeh Reservoirs in the Iranian part of the #Helmand (Hirmand) River Basin shared by Afghanistan and the I.R.Iran

— United Nations University-INWEH (@UNUINWEH) May 20, 2023

More info: https://t.co/5LSx7bnN8j pic.twitter.com/DLVueyEvBe

The Chah-Nimeh reservoirs are large natural holes in Sistan and Baluchestan province. Helmand River water is directed into these holes. They are the main sources of drinking water for Zabol, Zahak, and Zahedan cities.

“The death of Hamoun equals the death of the whole region,” Andik warned. “The barren lakebed could undoubtedly worsen the effects of the strong wind that blows for 120 days each summer in the region.”

“The winds cause debilitating sand and dust storms, and as dust particles can fly over 500 hundred kilometers they can affect south and southwest of Afghanistan and even northwest of Pakistan.”

Currently, the Sistan Basin is one of the main hotspots in terms of mineral dust emissions, according to a 2021 report by the United Nation Asian and Pacific Centre for the Development of Disaster Information Management (APDIM).

The report, assessing the risks sand and dust storms pose in the Asia and Pacific region, estimates that the costs of dust-related damage to electrical installations in the Sistan region, including cleaning and repairs, amounted to about USD 650,000 over the period 2000-2004.

“With an additional cost due to blackouts of almost USD 50,000 over the same period, the total cost to power supplies came to USD 0.69m over the five years,” it added.

Impact on agriculture

About 15 percent of Iran’s agricultural land is also exposed to dust deposition which can be detrimental to crops and have a significant negative impact on agricultural production, according to the APDIM report.

While most of the population in the region is fishers, livestock breeders or farmers, their livelihood depends on Hamoun, and its depletion forces them to move to other parts of the country in search of jobs, leaving villages uninhabited.

“Shortage of water hampers economic and social development in the province and results in the displacement of the population, not only in Iran but Pakistan and Afghanistan,” Andil stated.

The United States Geological Survey (USGS) says the average annual discharge on the Hirmand River Basin is about 6.12 million megaliters (million cubic meters).

“Iran is only entitled to 820 million cubic meters of the annual discharge of Hirmand River and not the basin which is not fully provided,” Andik noted.

“Based on the 1973 treaty Iran’s annual water share of Helmand is designated for drinking and agricultural purposes, however, Afghanistan, like any other country, is bound to provide the wetlands with their water rights to save them from turning into lifeless salt flats.”

Iran pursuing its water rights

In recent weeks, high-ranking Iranian officials have urged the de-facto Taliban government in Afghanistan to show its commitment to the water-sharing pact and honor Iran’s water rights.

On Thursday, Iranian President Ebrahim Raeisi, during his visit to Chabahar, a port city in Sistan and Balouchestan province, warned the Taliban authorities to take urgent measures and provide Iran’s water share.

“I warn the authorities and rulers of Afghanistan to swiftly fulfill the rights of the people of Sistan and Baluchestan Province and the Sistan region,” he said.

“If our experts confirm the lack of water, we have nothing else to say; otherwise, we will not allow the rights of our people to be violated.”

In a phone conversation on Wednesday, Iran’s foreign minister Hossein AmirAbdollahian discussed the issue with Amir Khan Muttaqi, the acting Afghan foreign minister, demanding Iran’s share of water.

Muttaqi, for his part, stressed that the country respects the 1973 treaty and will work to settle technical problems in this regard, according to the statement.

During a visit to Sistan and Baluchestan on Thursday, Amir-Abdollahian said that based on the 1973 treaty, Iran has a “natural right” to Hirmand River’s water and that Tehran would “seriously pursue” the matter.

“If necessary, pressure tools will be used against that part of Afghanistan’s ruling body that refuses to go along with granting Iran its water rights,” he was quoted as saying.

Later, in a tweet, Amir-Abdollahian slammed the Taliban government for not allowing an expert team to visit the region to investigate the claims about the shortage of water in the Hirmand River Basin.

“Over the past few months, I have repeatedly asked Muttaqi, the acting Afghan foreign minister to act according to the [1973] Helmand treaty and let technical delegations inspect water level, but they did not, Sistan is draught-stricken, what counts is a technical inspection not issuing political statements.”

Drought used as a pretext

According to Andik, while Afghanistan, pretty much like Iran, has been affected by long drought spells, studies conducted by Afghan researchers show that since the last “severe drought” in 2001, rainfalls have been “almost normal” in the Hirmand River Basin.

“As stated in the [1973] treaty between Iran and Afghanistan, Sistan and Balouchestan is entitled to its specified water rights in normal water years,” he told the Press TV website.

“Based on SPI indices, given in research carried out by Afghan researchers themselves, over the past 20 years the mean precipitation levels have not varied much.”

The Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) is a widely used index to characterize meteorological drought on a range of timescales.

Precipitation change in all Afghanistan river basins

There is speculation that Afghanistan is using drought spells and the water shortage as a pretext to not implement the 1973 treaty and not supply Iran its water share from Hirmand River Basin.

A video Andik posted on his Twitter account includes satellite images taken from the Kajaki dam on the Helmand River from mid-December to mid-May. It clearly shows the dam water supply increased day by day, which again proves what the Taliban says about the drought does not hold water.

ویدیوی زیر وضعیت #سد_کجکی در پنج ماه گذشته را نشان میدهد.

— Behnam Andik | بهنام اندیک (@BehnamAndik) May 18, 2023

تصاویر ماهوارهای به خوبی نشان میدهند که طی این مدت مخزن سد روز به روز پر آبتر شده است و این یعنی طالبان ادعایی خلاف واقع دارد.

تصاویر بازه زمانی ۲۴ آذر پارسال تا ده روز پیش با نشان میدهند.#سیستان_آب_ندارد https://t.co/Z5uyzsOrrs pic.twitter.com/IRetRtiXuo

On Thursday, Hossein Dalirian, the spokesman for the Iranian Space Agency said in a tweet that images captured by the Iranian-made Khayyam satellite show the Afghan government prevented water from reaching the Iranian side of the border in some places by creating numerous dams and diverting the flow of water.

Last August, Iran’s Department of Environment announced that the Taliban government in Kabul diverted the water stored behind Kamal Khan Dam on the Hirmand River to the Godzareh depression, instead of providing the share of water for the Hamoun wetlands.

Meanwhile, in a statement released on Friday, the Taliban authorities announced that there is not enough water behind Kamal Khan Dam to flow into Hamoun.

Hojjat Mianabadi, a Ph.D. in Hydropolitics, Water Diplomacy, and Water Conflict Management, said in a tweet on Friday that Kamal Khan Dam, with a storage capacity of 52 million cubic meters, is a diversion dam.

A diversion dam, as the name suggests, diverts all or a portion of the flow of a river from its natural course to an artificial watercourse, a canal, another river, etc, for irrigation purposes or electricity production.

Therefore, Mianabadi explained, scientifically, the lack of water behind a diversion dam does not support claims about drought spells in Afghanistan.

Even so, drought spells do not justify the Taliban’s violation of the treaty and not providing Iran with its share of water, he said, adding that based on the treaty in years when drought hits, Iran’s share of water should decrease accordingly, rather than cutting off completely.

‘No compromise’ on water share

On Sunday, Iran’s parliament speaker, Mohammad Baqer Qalibaf, in a strongly-worded statement said there will be “no compromise” on Iran’s water share from the Hirmand River.

Qalibaf urged the Afghan authorities “to deliver a constructive response to Iran’s positive will in this regard and prevent a serious problem in bilateral ties given sufficient water reserves on Afghan soil.”

Iran’s energy minister Ali Akbar Mehrabian also said on Friday that given the supply of water stored in the Kajaki dam and the terms of the 1973 treaty, Afghanistan is obliged to provide Iran’s share of water.

“Water is available at the upstream and our data as well as international data confirm that Afghan rulers have also confirmed that there is a supply of water in Kajaki dam,” he remarked.

He said if Afghanistan has not violated the treaty and did not add any constructions to divert the flow of water, there are no technical issues left to prevent the water from filling Hamoun wetland in Iran.

On Friday, Kazemi Qomi said Afghanistan’s Taliban government has to commit to the 1973 treaty and supply Iran with its share of water from the Hirmand River within a month.

“If it is proven that there is enough water in dams built on the Helmand River and the Taliban has refused to provide it, the Iranian government knows how to stand up for its rights,” he warned.

Yemeni armed forces down F-18 fighter jet, repel US-UK attack: Spokesman

Iran warns against US-Israeli plot to weaken Muslims, dominate region

VIDEO | Public uproar in US against Israeli regime

‘Ghost town’: 70% of Jabalia buildings destroyed by Israel

Mother’s Day: Sareh Javanmardi’s inspiring journey as Paralympic champion and mother

Russia downs over 40 Ukrainian drones as Putin vows 'destruction' on Kiev

VIDEO | Yemen: A bone in Israeli neck

D-8’s role in Iran’s economy after Cairo summit

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website