Emergency re-imposed in Sri Lanka ahead of parliament vote for new president

Sri Lanka’s acting president Ranil Wickremesinghe on Monday again declared a state of emergency in the crisis-hit island nation in an attempt to quell social unrest ahead of a parliamentary vote to elect the new president.

Announcing the move in a statement, the interim president stressed that the decision was “expedient” to protect public security and supplies.

“It is expedient, so to do, in the interests of public security, the protection of public order and the maintenance of supplies and services essential to the life of the community,” the statement said.

Wickremesinghe, who was sworn in as the country's interim president until parliament picks a successor to Gotabaya Rajapaksa, also declared a curfew in the capital Colombo and beyond in the western province.

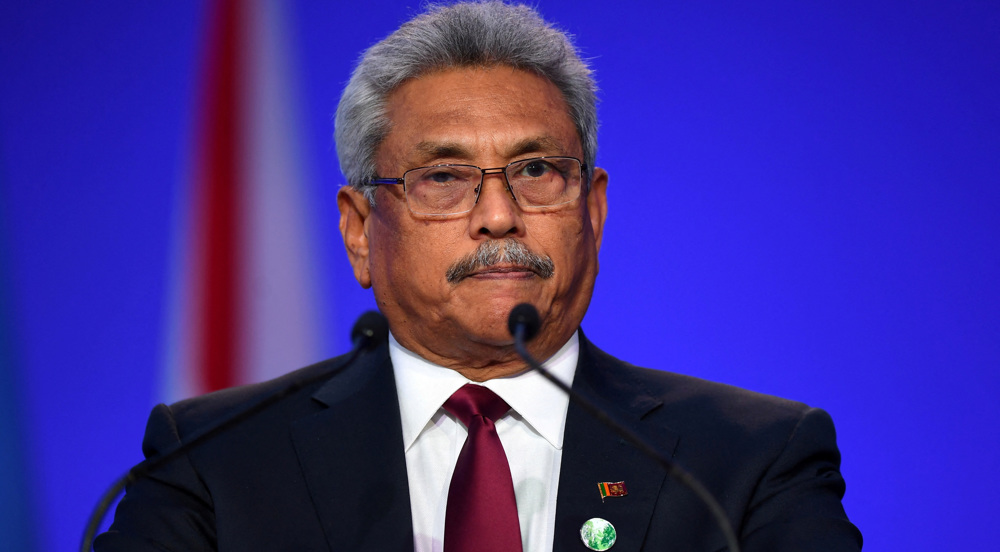

Rajapaksa resigned after mass protests over the island nation's economic collapse forced him to flee the country.

Parliament Speaker Mahinda Yapa Abeywardana has vowed a swift and transparent political process that will be complete within a week.

The new president could appoint a new prime minister, who would then have to be approved by parliament.

The development comes on the heel of other restrictive measures imposed by Sri Lanka's beleaguered leaders since April, when people rallied in the streets to protest against the government's handling of a deepening economic and financial crisis.

Previous emergency regulations involved the military to take positions at the streets to arrest and detain people, search private property and dampen public protests.

Wickremesinghe had announced a state of emergency last week after the popular uprising forced Rajapaksa to flee the country and tender his resignation from exile.

It was not clear whether that order had been withdrawn or had lapsed, or whether Wickremesinghe had reissued the order in his capacity as acting president.

Bhavani Fonseka, senior researcher at the Centre for Policy Alternatives, was quoted as saying that declaring a state of emergency was becoming the government’s default response, in spite of proving to be “ineffective”.

The island of 22 million people is struggling with its worst economic crisis since independence in 1948 amid a severe foreign exchange shortage that has limited essential imports of food and medicine and has, in turn, erupted wide range of protests.

At least one person died and 84 others were injured earlier this month amid biggest demonstrations seen since the protests first began in April.

Soaring inflation, at a record 54.6 percent in June and expected to hit 70 percent in the coming months, has heaped hardship on the population.

The shortage of foreign exchange has also caused a fuel crisis across the country. However, the south Asian country received its first of three fuel shipments on Saturday, providing some relief to the crisis-stricken people.

Mother’s Day: Sareh Javanmardi’s inspiring journey as Paralympic champion and mother

Russia downs over 40 Ukrainian drones as Putin vows 'destruction' on Kiev

VIDEO | Yemen: A bone in Israeli neck

D-8’s role in Iran’s economy after Cairo summit

China slams US as ‘war-addicted’ threat to global security

China ‘firmly opposes’ US military aid to Taiwan

VIDEO | Press TV's News Headlines

President Yoon Suk Yeol to be removed from office

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website