Worst drought in decades devastates Ethiopia's nomads

There has hardly been a drop of rain in Hargududo in 18 months. Dried-up carcasses of goats, cows and donkeys litter the ground near the modest thatched huts in this small village in the Somali region of southeastern Ethiopia.

The worst drought to hit the Horn of Africa in decades is pushing 20 million people towards starvation, according to the UN, destroying an age-old way of life and leaving many children suffering from severe malnutrition as it rips families apart.

April is meant to be one of the wettest months of the year in this region. But the air in Hargududo is hot and dry and the earth dusty and barren.

Many of the animals belonging to the 200 semi-nomadic herder families in the village have perished.

Those who had "300 goats before the drought have only 50 to 60 left. For some people... none have survived," 52-year-old villager Hussein Habil told AFP.

The tragic story is playing out across whole swathes of southern Ethiopia and in neighbouring Kenya and Somalia.

In Ethiopia, the eyes of the world have largely focused on the humanitarian crisis in the north caused by the war between government forces and the Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF) that has left nine million people in need of emergency food aid.

But the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) estimates that up to 6.5 million people in Ethiopia -- more than six percent of the population -- are also severely food insecure because of drought.

Lack of rain has killed nearly 1.5 million head of livestock, around two-thirds of them in the Somali region, said OCHA, showing "how alarming the situation has become".

Herds provide the nomadic or semi-nomadic populations of this arid and hostile region with food and income as well as their savings.

But the surviving animals have deteriorated so much that their value has plummeted, reducing the buying power of the increasingly vulnerable households, OCHA warned.

Society 'disintegrating'

"We were pure nomads before this drought, depending on the animals for meat, milk" and money, said 50-year-old Tarik Muhamad, a herder from Hargududo, 50 kilometres (30 miles) from Gode, the main town in the Shabelle administrative zone.

"But nowadays most of us are settling down in villages... There is no longer a future in pastoralism because there are no animals to be herded."

An entire society is disintegrating as the loss of livestock threatens the herders' very way of life: villagers forced to leave their homes to find work in the city, families divided, children neglected as their parents focus on trying to save their animals, essential for their survival.

"Our nomadic life is over," Muhamad said bitterly.

The alternating dry and rainy seasons -- a short one in March-April followed by a longer period between June and August -- have always set the rhythm of herders' lives.

"Before this catastrophic drought, we used to survive difficult times thanks to the grasses from earlier rains," the herder said.

But none of the last three rainy seasons have come. And the fourth one, expected since March, is likely to fail too.

"We usually have droughts, it's a cyclical thing... previously it used to be every 10 years but now it's coming more frequently than before," said Ali Nur Mohamed, 38, from British charity Save the Children.

Even camels lose their humps

In East Africa, the frequency of drought has doubled from once every six years to once every three since 2005, according to the latest UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report.

"Several prolonged droughts have occurred predominantly within the arid and semi-arid parts of the region over the past three decades."

As early as 2012, a study by US development agency USAID found that southern regions of Ethiopia were receiving 15 to 20 percent less rainfall than in the 1970s. And those areas that did get the 500 millimetres of annual rainfall needed for viable agriculture and livestock farming were shrinking.

Drought will be high on the agenda of the UN Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD), which begins in Abidjan on Monday.

Herders trying to recover from a drought are being "hit by a second drought", said Save the Children's Mohamed.

"So it makes it impossible for them to recover quickly from the previous shocks." The droughts come "so close that these pastoralists are unable to be resilient."

The herders AFP met in the Somali region say they have lost between 80 and 100 percent of their livestock. The few herds of cows or goats we spotted were emaciated.

Even many dromedaries have lost their humps, the vital stores of fat that enable them to survive for long periods without food.

- 'Walked for five days' -

Many herders have moved to camps that have sprung up to house the vast numbers of people displaced by what they describe as the worst drought they have ever seen.

In the morning light in Adlale, not far from Gode, dozens of women in coloured veils emerge from clouds of ochre dust to collect emergency food aid distributed by the UN's World Food Programme (WFP).

"We walked for five days to come here," said Habiba Hassan Khadid, a 47-year-old mother of 10. "All of our livestock perished because of the drought."

Ahado Jees Hussein, 45, a widowed mother of seven, arrived in Adlale carrying her 15-year-old disabled son on her back. She tells a similar story of losing all her goats and pack donkeys.

"I have never before experienced such a drought," she said. "I came here with nothing."

About 2,700 families are living in the camp known as Farburo 2, which was set up three months ago.

Small huts made of branches and patchworks of fabric provide some shelter from the searing heat, with temperatures close to 40 degrees Celsius (104 Fahrenheit).

"The living conditions are alarming," said camp coordinator Ali Mohamed Ali, as most of the families scrape by on what they get from relatives or from local residents.

'Way of life can't continue'

In his tiny hut, Abdi Kabe Adan, a sturdy and proud 50-year-old, weeps uncontrollably and prays to Allah for the rains to come.

"Before, rain fell elsewhere in the region, so we moved with our animals to watered pastures, even if it took several days.

"But this time the drought is everywhere... Wells have run out of water, no pastures for animals to graze. I don't think it's possible for our way of life to continue," he sobbed.

"I have seen goats eating their own faeces, camels eating other camels. I have never seen that in my life."

There are few men in the camp. Some have stayed with the last of the cattle in the hunt for elusive grass, but many have left in search of work in town.

Others have simply fled, unable to face the shame or the questions about the future from their anxious wives.

The drought has also damaged the social structure of these communities.

"Before, the men had honoured chores like milking the animals, buying food and goods for the family. These roles have disappeared along with our livestock," said Halima Harbi, a 40-year-old mother of nine.

Solidarity in the face of diversity has given way to rivalry, she said. "When the water trucks arrive, the old and vulnerable receive nothing because competition is fierce."

- 'No time to care for children' -

Children are paying the highest price as the disaster worsens.

UNICEF executive director Catherine Russell said 10 million children across Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia and Djibouti needed urgent life-saving support.

As well as a malnutrition crisis, "children are forced to drink contaminated water, putting them at risk of cholera and other killer diseases," said Russell, who visited the Somali region last week.

Another heartbreaking consequence of drought, she said, is an increase in child marriage "as families marry off their daughters in the hope they will be better fed and protected as well as to earn dowries."

"People don't even have time to look after their children," said Ali Nur Mohamed of Save The Children.

"You can understand the magnitude of the problem... (when) a mother forgets to take her (sick) child to the nearest hospital ... because she is preoccupied with her other children or trying to save her livestock."

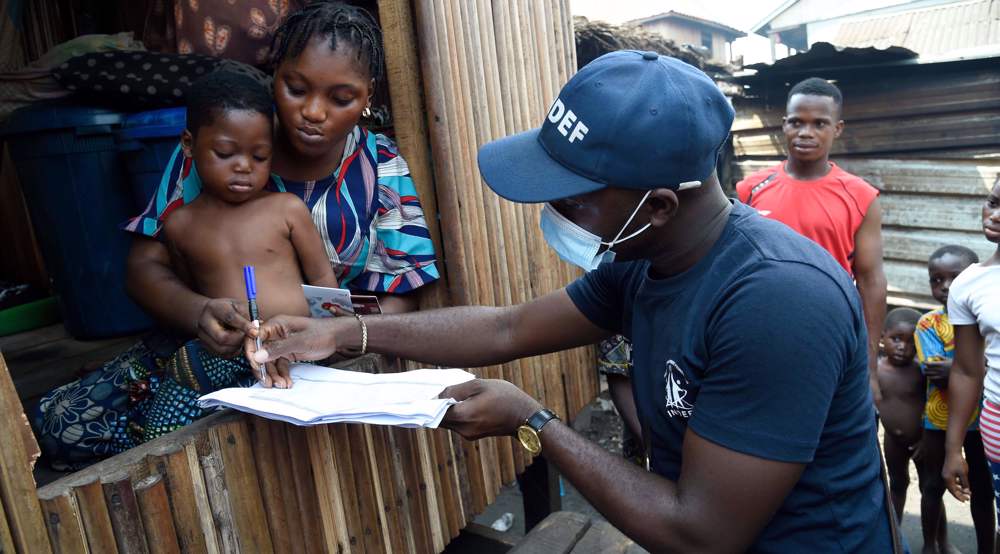

Save the Children staff do the rounds in the communities, identifying children at risk and taking them for treatment to health centres, such as the hospital in Gode.

In the stifling air of the hospital's nutrition unit, mothers sit on iron-framed beds, using their veils to try to keep themselves and their painfully thin children cool and repel the flies.

Hospital director Dr Mahamed Shafi Nur said children in the region are already on the verge of malnutrition, so if they get sick, they cross the danger line.

Most are treated on an outpatient basis, given ready-to-eat peanut-based nutritional pastes. Those who suffer complications -- about 15 percent -- are hospitalised.

Paediatrician Dr Mahamad Abdi Omar says mothers often find themselves alone with their offspring as the father hunts for food for their animals. So by the time they are able to bring a sick child to hospital, there are added complications.

- Heart-wrenching choices -

Baby Samiya had been suffering from diarrhoea and vomiting for a week before her mother Rokiya Adan Mahad, 39, finally brought her into the clinic.

Falis Hassen's son has been suffering from canker sores for two months, preventing him from suckling.

The 38-year-old said she came to the hospital without telling her husband. "He wouldn't have let me leave, there is so much to do."

Abdullahi Gorane's son, his hair discoloured by malnutrition, had been suffering from diarrhoea and vomiting for weeks.

"I was taking care of the livestock, I didn't have time for my child," said 30-year-old Abdullahi -- the only father present -- who decided to bring in his son only when the drought took most of his herd.

Ahmed Nur, a health worker at the Kelafo clinic about 100 kilometres (60 miles) from Gode, said one of the issues is a lack of "exclusive breastfeeding" -- mothers give their newborns water or sugar instead so the babies do not get enough milk.

But the situation has been aggravated by the drought.

"Every month, the number of malnourished kids is increasing," he said.

Parents like Ayan Ibrahim Haroun, 45, are confronted with terrible choices: treating their child can mean risking the loss of their livestock.

She said her two-year-old daughter Sabirin Abdi had been sick for a month -- constant coughing and swellings on her little body (a possible symptom of severe malnutrition) -- when she finally resolved to bring her to Kelafo.

"I had 10 goats, but I lost four in the 11 days I was at the hospital," she said.

(Source: AFP)

Turkey's foreign minister meets Syria's de facto leader in Damascus

'Next to impossible' to rescue patients from Gaza's Kamal Adwan Hospital: Director

VIDEO | Vietnam current prosperity

Report blames gasoil exports for shortage at Iranian power plants

VIDEO | Hind Rajab Foundation names Israeli war criminals vacationing after Gaza genocide

VIDEO | Australians rally for Gaza ahead of Christmas festivities

VIDEO | Attacks on Sana'a

Iran reports further drop in annual inflation rate in December

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website