Scientists expect more worrisome variants after Omicron

Scientists have warned that Omicron’s whirlwind advance won’t be the last variant of the coronavirus this year and that it’s difficult to predict how quickly the new variant would spread.

Experts don’t know what the next variants will look like or how they might shape the pandemic, but they say there’s no guarantee the sequels of Omicron will cause milder illness or that existing vaccines will work against them.

As Omicron appears to cause less severe disease than Delta, its behavior has kindled hope that it could be the start of a trend that eventually makes the virus milder like a common cold.

It’s a possibility, experts say, given that viruses don’t spread well if they kill their hosts very quickly. But viruses don’t always get less deadly over time.

When new variants develop, it is difficult for scientist to say which virus might take off from its genetic features.

For example Omicron carries about 30 mutations in its spike protein that lets it attach to human cells, many more than previous variants. But the so-called IHU variant identified in France and being monitored by the WHO has 46 mutations and doesn’t seem to have spread much at all.

Another potential route: With both Omicron and Delta circulating, people may get double infections that could spawn what Dr. Stuart Campbell Ray, an infectious disease expert at Johns Hopkins University calls “Frankenvariants,” hybrids with characteristics of both types.

Ray likened vaccines to armor for humanity that greatly hinders viral spread even if it doesn’t completely stop it and said when vaccinated people get sick, their illness is usually milder and clears more quickly, leaving less time to spawn dangerous variants.

The World Health Organization reported a record 15 million new COVID-19 cases for the week of January 3-9, a 55% increase from the previous week.

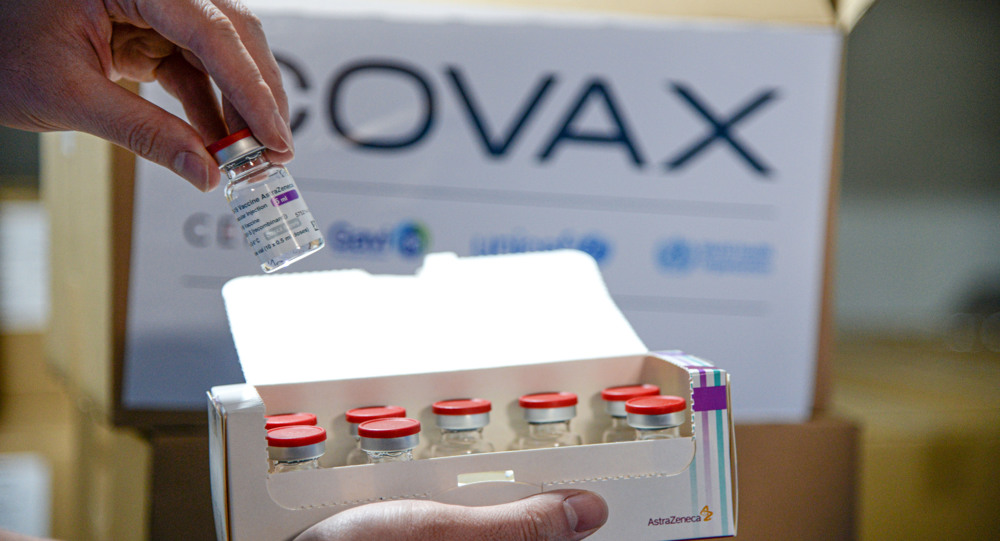

Experts say the virus won’t become endemic like the flu as long as global vaccination rates are so low.

During a recent press conference, WHO Director General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said that protecting people from future variants — including those that may be fully resistant to today’s shots — depends on ending global vaccine inequity.

Israel preparing to stay in southern Lebanon after ceasefire: Report

Israeli pressure on Hamas ‘hardly helped’; swap deal necessary: Ex-Mossad chief

Far-right Israeli minister Ben-Gvir again storms al-Aqsa Mosque

Iran: Israel’s attack on journalists’ vehicle in Gaza amounts to ‘war crime’

VIDEO | Israel’s war spending

Palestine Action wins again

VIDEO | Palestinian Authority's blockade of Jenin refugee camp reaches third week

Dec. 25: ‘Axis of Resistance’ operations against Israeli occupation

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website