Panjshir, the last anti-Taliban holdout, faces long odds

By Syed Zafar Mehdi

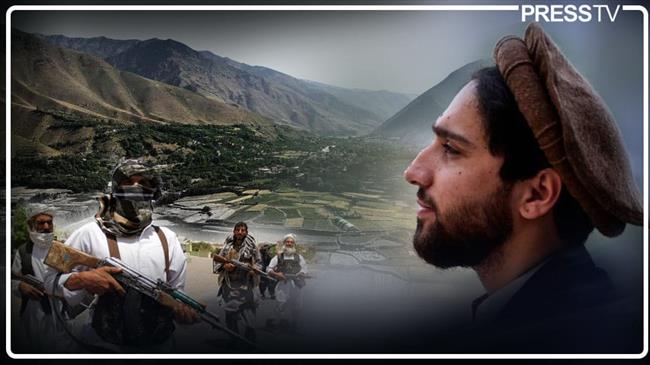

A silent anti-Taliban rebellion is brewing in the rugged mountains of northern Afghanistan’s picturesque Panjshir valley, which has traditionally been the fortress of Afghan resistance forces.

The quaint valley nestled in the majestic Hindu Kush Mountains, 150 km north of Kabul, is home to a largely ethnic Tajik population. Known for its lush-green meadows and gushing streams, the valley has long been the graveyard of invaders, from the Greeks to Sikhs, British, Soviets and the Taliban.

According to a fascinating legend, sometime in the 10th century AD, five brothers built a spectacular dam in the valley on the orders of Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni, after which they earned the sobriquet of ‘Panjshir’ (Five Lions). The valley adopted the same name.

Panjshir has over the centuries produced many legendary warriors who single-mindedly resisted and repelled attacks from foreign invaders. They were helped by the valley’s unique topography and strategic location, which made the task difficult for powerful invading armies.

When the Soviets went on a rampage in Afghanistan in 1980s, they could not lay siege to this Hindu Kush valley. When the Taliban swept to power in 1990s, the difficult mountainous terrain dissuaded them from making inroads there.

The man who spearheaded the fight, first against the Soviets and then against the Taliban – Ahmed Shah Massoud – came to be known as ‘Sher-e Panjshir’ (The Lion of Panjshir) for his battlefield heroism.

After the Taliban captured Kabul in 1996, Massoud, who was then the Defense Minister in President Burhanuddin Rabbani’s government, retreated to Panjshir along with his close associates.

The militant group made stunning advances across the country, but failed to capture Panjshir where the Northern Alliance led by Massoud put up a spirited resistance.

Having earned fame for leading ‘Mujahideen’ fighters against the Soviets in 1980s, resistance against the Taliban, which was led by shadowy figurehead, Mullah Omar, catapulted him to global stardom.

His key ‘jihadi’ associates included those who went on to assume key political positions in years to come – Abdullah Abdullah, Ata Mohammad Noor, Marshal Fahim, Yunus Qanooni, Abdul Rashim Dostum and Amrullah Saleh.

As fate would have it, Massoud’s eventful journey was short-lived.

Two days before the cataclysmic events of 9/11, the legendary anti-Taliban commander was assassinated. Posing as filmmakers, the al-Qaeda assassins sat down with Massoud for an interview before the explosives hidden in the camera and battery pouch blew up everything.

Soon after the 9/11 attacks, then US President George Bush ordered the invasion of Afghanistan on the pretext of taking out the alleged 9/11 mastermind, Osama bin Laden, who was believed to be hiding in the mountains of Afghanistan, hosted by the Taliban.

The Taliban were toppled and Bin Laden was later found in another country, but the foreign invaders refused to end the military occupation of Afghanistan, which eventually paved the way for Taliban’s astonishing resurgence. The militant group, which had in 2001 offered to give up arms and recognize the US-backed Hamid Karzai government, in 2021 forced Americans to beat a humiliating retreat.

In recent weeks, as we have seen, the Taliban has made a stunning comeback, toppling the US-backed government in Kabul and seizing control of the war-ravaged country.

The only terrain that is yet to be overrun by the marauding Taliban fighters is the Panjshir valley.

This time it’s the son of Ahmed Shah Massoud – Ahmed Massoud – leading new resistance against the same old militant group. There is no Mullah Omar anymore and there is no Northern Alliance either. Massoud’s resistance fighters of 1990s have become unscrupulous politicians in 2021.

When the Taliban took power in 1990s, the Northern Alliance was a formidable force, backed by many regional countries. It held much of the country’s north, including the strategic Badakhshan province.

This time, the dynamics have changed. The game is heavily tilted in favor of the Taliban, who are at their strongest ever. On the other hand, the Northern Alliance is dead and most of its famed fighters-turned politicians are in hiding. Many of them have tamely surrendered.

The young Massoud, who has his father’s one-time allies like former vice president, Amrullah Saleh, and former defense minister, Bismillah Mohammadi, on his side, is banking on the support of local anti-Taliban militia fighters and former Afghan security forces who have found refuge in Panjshir.

The National Resistance Front (NRF), the new avatar of the Northern Alliance, boasts of a large stockpile of equipment, vehicles and weapons to fight the Taliban. There are also unconfirmed reports of helicopters from neighboring Tajikistan delivering arms and ammunition to them.

But the question is: Will Massoud and his associates be able to withstand an attack from a much superior armed force and can they mobilize the kind of support the Northern Alliance had in 1990s?

“We will sacrifice our lives, but we will not sacrifice our land and our honor,” Massoud, the graduate of Kings College and Sandhurst Military Academy, told his supporters in Panjshir earlier this week. He has reportedly built an army of 6,000 fighters.

“We want to make the Taliban realize that the only way forward is through negotiation,” he was quoted as saying in media. “We do not want a war to break out.”

Even with history being on his side and the advantage provided by geography, Massoud realizes that it is an uphill task under present circumstances. War seems to be the last option. He is batting for an “inclusive, broad-based government” in Kabul that represents different ethnic groups.

At the same time, the legacy of his legendary father sits heavily on his young shoulders. He may not like direct military confrontation with the Taliban, but he doesn’t want to retreat or surrender.

There are reports that the Taliban fighters are already advancing toward Panjshir. The group has claimed that they are in control of at least three districts around the Hindu Kush valley.

Saleh, who has declared himself the new caretaker president after his boss fled the country, on Tuesday warned the Taliban to “avoid the terrains” to Panjshir, while acknowledging that the militant group has “amassed forces near the entrance of Panjshir.”

He served as Ahmed Shah Massoud’s liaising officer with international spy agencies in 1990s and later went on to head Afghanistan’s spy agency in mid 2000s. In the last few years, his politics has vacillated between Panjshir and Kabul. To the surprise of many, he became Ghani’s running mate in last year’s presidential election against his long-time friend and fellow Panjshiri Abdullah Abdullah.

“I will never, ever and under no circumstances bow to the Taliban terrorists. I will never betray the soul and legacy of my hero Ahmad Shah Massoud, the commander, the legend and the guide,” he wrote on Twitter last week, a clear attempt to woo back Panjshiris.

Saleh hasn’t publicly backed the Massoud-led resistance, but pictures circulating on social media have shown them holding meetings in their hometown. While both are putting up a tough front, they know odds are heavily against them.

Unless the two warring sides work out a compromise, the Taliban attack on the valley that has become the focal point for resistance against the militant group looks imminent. And this time, the Taliban may create history by traversing the valley’s difficult and dangerous terrains.

Syed Zafar Mehdi is a Tehran-based journalist, editor and blogger with over 12 years of experience. He has reported extensively from Kashmir, India, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Iran for leading publications worldwide.

(The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect those of Press TV.)

Hamas thanks Iran, Resistance Front following achievement of ceasefire in Gaza

'Capitulation': Israeli officials and media concede Gaza defeat as truce unfolds

'Gaza has won': Social media users react to ceasefire with mix of relief, joy

Iran seeks South Korea’s assistance for AI, fiber-optic projects

VIDEO | Iran's 'Eqtedar' (Power) maneuver

Israel hits HTS military target in Syria for 1st time since fall of Assad

VIDEO | Press TV's news headlines

Israel has slaughtered 13,000 students in Gaza, West Bank

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website