Discovery of children's remains at school site reopens wounds for indigenous survivors

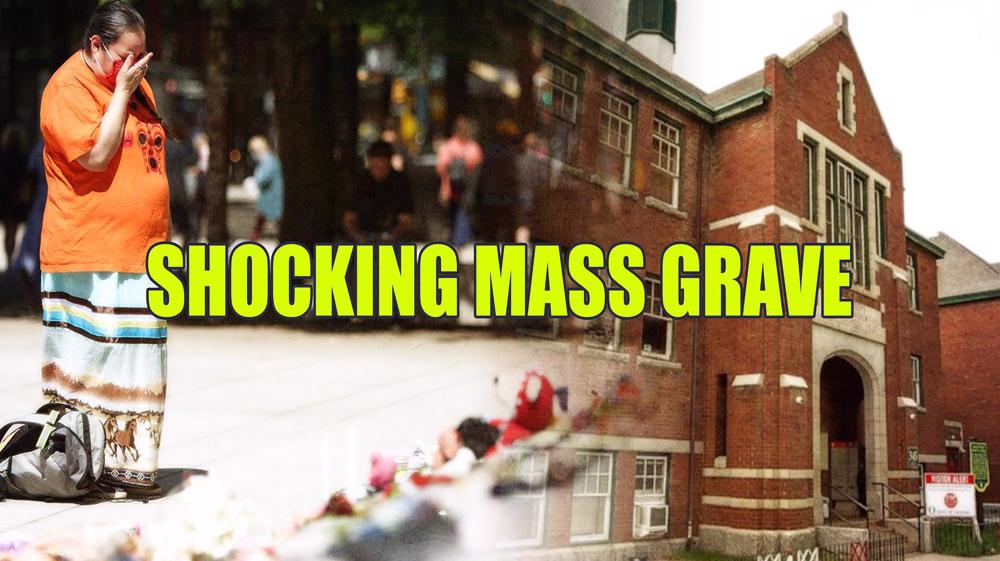

The discovery of remains of scores of indigenous children at a former residential school in Canada has reopened wounds among indigenous survivors of colonial Canadian schools.

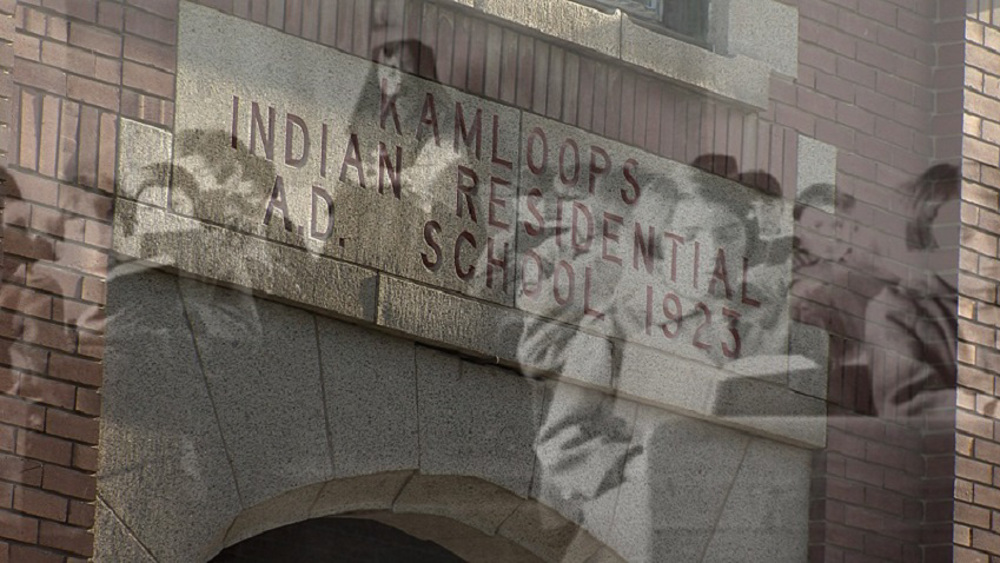

The discovery was announced by the chief of the Tk'emlups te Secwepemc First Nation — the home community of the Kamloops Indian Residential School— last Thursday.

Chief Rosanne Casimir said they had found the remains of 215 children, some as young as three, buried on the grounds of the old school, near Kamloops, British Columbia.

Following the latest discovery, indigenous communities met across the country to figure out how best to investigate the remaining sites.

Canada’s residential school system forcibly separated more than 150,000 First Nations children from their families between 1831 and 1996.

The move was part of a program to assimilate the community into Canadian society.

The kids were subjected to abuse, malnutrition and rape in what the Truth and Reconciliation Commission tasked with investigating the system called “cultural genocide” in 2015.

The communities were forced to convert to Christianity and not allowed to speak their native languages.

Ceremonies to honor the victims took place or were to take place throughout the country.

One of the survivors, who spent his teenage years at the Kamloops Indian Residential School told Reuters on Thursday, “My life became hateful to me,” while remembering the hunger, loneliness and fear.

“I couldn't help but think it's monsters that done this, to put bodies in an unmarked grave site,” the 72-year-old St’at’imc Nation member added.

The development comes as the federal government has pledged to spend previously promised money on indigenous communities that want to search former school sites for the remains of children.

In 2019, the government promised C$33.8 million ($28.1 million) over three years to support, among other things, locating the bodies of children who attended the schools. Of that, C$27.1 million has yet to be spent.

Marta Hurtado, spokeswoman for the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), called the school discovery “shocking,” urging the Canadian government to “redouble efforts to find the whereabouts of missing children, including by searching unmarked graves.”

She also called for a legal entity to protect and manage burial sites.

Judy Wilson, Chief of the Neskonlith Indian Band, whose father was separated from his family when he was five years old, said she wants to see an independent investigation of this burial site and others, possibly involving the United Nations.

“This is a larger story beyond residential schools. They broke down our family structures, our governance, our nations, our communities. It's a travesty that our children bore the brunt of that genocide,” she said.

“Our villages were like ghost villages, with no children.”

Kamloops was one of 139 boarding schools that were set up a century ago to forcibly assimilate Canada's indigenous peoples. The Catholic Church ran many of the schools, and the Vatican has not apologized.

Lack of papal apology in indigenous school abuse 'shameful'

Meanwhile, Canada's Indigenous Services Minister Marc Miller said it is “shameful” that the Pope has never formally apologized for abuses at the country's Catholic-run indigenous residential schools.

“I think it is shameful that they haven't done it, that it hasn't been done to date,” he said. “It should be done. There is a responsibility that lies squarely on the shoulders of the Council of Bishops in Canada,” he said at a news conference on Wednesday, stressing that he supports growing indigenous calls for a papal apology.

He further termed the schools “labor camps,” adding that, “Calling them a school is probably a euphemism.”

Crown-Indigenous Relations Minister Carolyn Bennett also said a papal apology is needed to “unlock the healing” in indigenous communities.

“They want to hear the Pope apologize,” she said, urging Catholics across Canada to “ask their church to do better.”

Also on Wednesday, Vancouver Archbishop J. Michael Miller offered an apology. “The church was unquestionably wrong in implementing a government colonialist policy which resulted in devastation for children, families and communities.”

“In light of the heartbreaking disclosure of the remains of 215 children at the former Kamloops Indian Residential School, I am writing to express my deep apology and profound condolences to the families and communities that have been devastated by this horrific news,” Miller said in a post on his Twitter account.

“If words of apology for such unspeakable deeds are to bring life and healing, they must be accompanied by tangible actions that foster the full disclosure of the truth,” he said, pledging to make church records about the schools available.

A delegation of indigenous leaders had in 2009 met privately with Pope Benedict, who “expressed his sorrow” over the school harms to indigenous peoples.

Although the statement of regret was welcomed by the group as “significant,” they said it fell short of an official apology.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission later noted that it was “disappointing to survivors and others that the Pope (had) not yet made a clear and emphatic public apology in Canada for the abuses.”

Pope Francis's subsequent refusal in 2018 -- after Canada's parliament passed a motion again asking the pontiff to apologize -- drew a polite rebuke from Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, who said he was “disappointed” with the church's decision.

Taking office in 2015, Trudeau pledged to make Canada's almost 1.7 million indigenous people a priority of his government.

He said often that no relationship was more important to him than the one between Canada and indigenous communities.

Critics, however, say the mentions of indigenous issues in his stump speeches have either been brief or absent.

Canada arrests prominent activist over pro-Palestinian stance

US to seize 2nd Venezuelan plane held in Dominican Republic

Panama Canal denies claim of free passage for US vessels

Australian senator smeared by anti-Iran groups for saying Iranian women 'have a voice'

Hezbollah's display of power proved resistance cannot be eliminated: Iran parl. speaker

Israel escalates West Bank raids as official says regime seeking to complete Gaza genocide

Palestinian man dies in Israeli prison as Foreign Ministry urges intl. probe into regime’s crimes

Putin says not opposed to Europeans’ involvement in Ukraine talks

VIDEO | Iranian Kurdish protesters demand European action against PKK, PJAK terror

VIDEO | Israel expands offensive in northern West Bank, deploys tanks to Jenin

VIDEO | Spaniards fill streets of Cádiz in solidarity with Palestine

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website