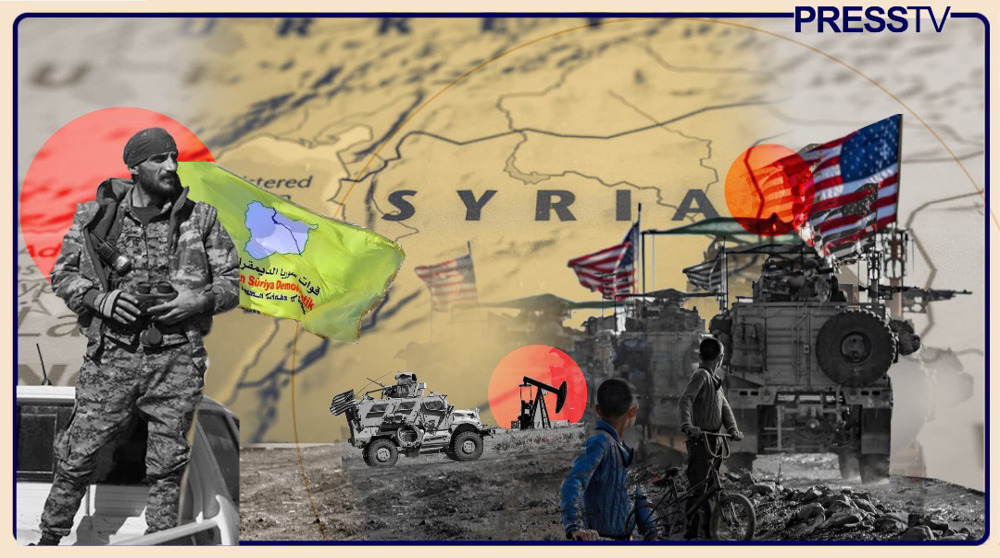

US and SDF join forces to steal Syria’s oil

By Jeremy Salt

There’s hardly anything new in history about the powerful exploiting the weak, so all that sticks out about the theft of Syria’s oil as orchestrated by the US government is its brazen nature.

"We’re keeping the oil," Donald Trump said in 2019. "I’ve always said that. We want to keep the oil. $45 million a month. We’ve secured the oil …. We’ll be deciding what to do with it in the future."

In 2011, the US and its allies set out to destroy Syria. A decade later, they had failed to overthrow the government in Damascus, while generating a conflict that had devastated the country and killed hundreds of thousands of Syria’s people. Their allies on the ground were the most vicious armed groups on the face of the planet.

Outside the destroyed towns and cities, Syria’s agricultural sector was also ravaged. Once the granary of the Roman empire, Syria was self-sufficient in wheat production at the start of 2011. As the war continued, agricultural production fell. While land being fought over could not be tilled, the weapons of war included the burning of cereal crops and arson attacks on bakeries. As late as 2020, 35,000 hectares of land under government control were ruined by fire.

After US intervention, the fertile Jazira region, accounting before 2011 for more than 17 percent of Syria’s agricultural production, mostly wheat and cotton, was brought under the control of the Kurdish "Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES)." Between them, the US and Kurdish administration now jointly control 90 percent of Syria’s oil reserves.

Economic sanctions against Syria were first declared in 1979, after Syria recognized the revolutionary Islamic government in Iran. Over the years, the sanctions have been progressively tightened, the two major measures being the Syrian Accountability and Lebanese Sovereignty Restoration Act (2003) and the even more lethal Caesar Syria Civilian Protection Act (2019), which, far from protecting Syria’s civilians, has done them immense harm.

The Syrian government can now meet only 20 percent of the domestic demand for wheat and cannot import sufficient quantities to close the gap. Bread rationing and queues are now a feature of daily life, with other food staples such as meat and cheese available at prices that are prohibitive for many. A black market is available to sell fuel, fertilizer, and other goods at a far higher price than what might be available through government channels.

The World Food Program (WFP) estimated recently that 12.4 million Syrians were food insecure: 46 percent of households were cutting down on their daily food intake, with many adults reducing consumption for the sake of their children.

As the result of war and sanctions, progressively tightened to squeeze the life out of the Syrian state and society, the currency is in a state of collapse. At the beginning of 2011, the Syrian pound was traded at 50 to the $US; by early 2015, it was being traded at 530 to the $US; by January 2020, 1200 to the $US; by the summer of 2020, 3000 to the $US; and by March, 2021, 4000 to the $US.

Syrian businessmen have billions of dollars in Lebanese banks, but can’t access them, undoubtedly because of US pressure, but also because of capital controls, in a country which has its own severe economic problems, including a lira recently trading at 10,000 to the $US. Lebanon itself is also suffering from US sanctions, targeting individuals, banks, and corporations connected with Hezbollah.

The US now controls 90 percent of Syria’s oil production, across an arc of territory stretching norhwards from the eastern region of Deir al-Zawr. Oil previously stolen by Daesh is now being stolen under the aegis of an occupying power, at a loss to the Syrian state so far of $92 billion in revenue. Having done all it can to destroy the Syrian economy, the US administration is now doing all it can to prevent economic recovery.

The theft of Syria’s oil is a collaborative effort between the US administration, a US limited liability oil company (Delta Crescent Energy), and the Syrian and Iraqi Kurdish political leaderships. Registered in Delaware, Delta Crescent, while claiming “decades of experience in oil and gas development” on its website, was only incorporated on February 8, 2019.

To operate in Syria, it first had to be given a waiver by the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) which in its executive order 13582, dated August 17, 2011, ruled that “specific” licenses could be issued to US nationals to engage in telecommunications, agricultural, and petroleum/petroleum products” in Syria, with benefits from the latter going to “the National Coalition of Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces and its supporters.” In fact, there was no such coalition in August, 2011: a makeshift group, it was cobbled together only in November, 2012.

After a year of negotiations, Secretary of State Pompeo was able to tell the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on July 30, 2020, that a US company was “in implementation” of a deal to begin operations in the Syrian “oil industry.” On August 2, Reuters reported that this unnamed US oil company had signed a deal with “Kurdish-led rebels. ” Lindsey Graham, a South Carolina Republican, told the Foreign Relations Committee he had been informed by Mazloum Abdi, the commander of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), the largely Kurdish militia collaborating with the US, that the deal allowed the company to “modernize the oilfields” in northeastern Syria. Asked whether the government was supportive he said “We are.”

Born in 1967 as Farhad Abdi Shahin but known intermittently as Shahin Tchelo and General Mazloum Kobani, Mazloum joined the Turkish PKK (Kurdistan Workers’ Party) in 1990, and was reported to be close to its founder, Abdullah Ocalan, long since imprisoned on an island in the Sea of Marmara. Abdi commanded the group’s "special forces" and was arrested a number of times in Syria before moving to Europe in 1997. He stayed there until the invasion of Iraq in 2003, when he returned to the Middle East, initially to Iraqi Kurdistan.

He rose to prominence in the Syrian Kurdish militia, the YPG (People’s Protection Units), and in 2014, travelled to Washington to negotiate a "Kurdish alliance against Daesh." The Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) were formed in October, 2015. In October, US and SDF forces "liberated" Raqqah from Daesh but not before 80 percent of the city had been destroyed by US aerial bombardment. From the point of view of the Syrian government, of course, the illegal occupation of the city had simply changed hands.

By March 2019, US-SDF forces had taken control of Baghouz, the last Daesh holdout in the eastern Deir al-Zawr Province, the location of most of Syria’s oilfields, including its biggest (al-Umar).

By August 2020, it was known that Delta Crescent Energy was the company authorized by the OFAC to “engage” in transactions in the Syrian oil industry. Its chief executives were James Cain, a Republican donor and US ambassador to Denmark during the George W. Bush presidency; John P. Dorrier Jnr., a “veteran” of the oil industry, as described in the media, also a Republican donor; and James Reese, a Delta Force veteran and senior advisor to the CIA for special operations in Afghanistan, his particular job being to integrate CIA and military elements during the invasion of Afghanistan and Operation Enduring Freedom (2001-2014), the codename for the "global war on terrorism."

After leaving the army (as an 80 percent disabled veteran), Reese founded the TigerSwan security consultancy, specializing in “risk mitigation” and “crisis management.” Under these headings, TigerSwan played an active role in infiltrating Native American-led protestors trying to stop the construction of the North Dakota Pipeline in 2016-2017. This was done without a permit, the North Dakota Private Investigation and Security Board having refused to issue one because of the “positive criminal history of one or more disqualifying offences” that had not been disclosed.

These apparently referred to several citations issued against Reese, one for reckless driving and others arising from a troubled marriage, including assault on a female (his wife), which was later dropped.

In an interview with CNN, Cain said Delta Crescent Energy had been “authorized” (by an occupying power) to “engage in all aspects of energy development, transportation, marketing, refining, and exploration” in northeastern Syria “in order to develop and redevelop the infrastructure in the region and to help the people of the region get their products into the international market.” (‘Former Army Delta Force officer, US ambassador sign secretive contract to develop Syrian oilfields,’ CNN Politics, August 5, 2020). Expected to generate billions of dollars for Kurdish authorities, the 25-year contract, CNN commented, was in line with Trump’s “longstanding goal” of securing US control over oilfields in the region.

Interviewed on Fox News in 2018, Reese reinforced Trump’s view that somehow northeastern Syria belonged to the US rather than being Syrian sovereign territory. “We own the whole eastern part of Syria,” he said. “If you take a line from Kobane and run it down the Euphrates River all the way back [to Iraq?] … That’s ours. We can’t give that up.” The spoils will be shared with a Kurdish "administration" claiming to represent an ethnic minority constituting 5-10 percent of the Syrian population.

Human rights groups have accused the Syrian Kurds of ethnic cleansing (the same complaint was made against the Iraqi Kurds after the invasion of 2003). In 2019, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov accused the US of attempting to resettle Syrian Kurds in Arab tribal areas, which he described as a “direct way to separatism and the breakup of Syria.” (‘Lavrov: US attempts to settle Kurds in Arab areas might trigger Syria’s breakup,’ Tass News Agency, May 8, 2019).

Even before given the OFAC waiver, Cain and Reese went to northern Iraq to stitch up the Iraqi Kurdish side of the deal. Photos show them meeting the governor of Dohuk Province Samaan Atroche in 2018 as well as senior figures in the Kurdish Democratic Party (KDP), including Nechirvan Barzani, current president and former prime minister of the Kurdish Regional Government. Jim Jeffrey, the US ‘special representative for Syria engagement,’ also had talks with Barzani to help seal the deal.

In February 2021, Bassam Tu’ma, Syria’s oil and mineral resources minister, said that of the 89,000 barrels of crude oil produced in Syria in 2020 (compared to the 380,000 barrels a day produced before the war), 80,000 barrels had been stolen. Since late 2020, hundreds of tankers from Deir al-Zawr and Hasakeh guarded by SDF forces have been carrying plundered Syrian oil into northern Iraq through the Mahmudiya crossing. In February, the Syrian governor of Hasaka Province, Ghassan Halil Khalil, told a Lebanese newspaper that the SDF was “stealing” 40,000 barrels of oil a day.

While the US admits a military presence near the Syrian oilfields, it denies that it is ‘protecting’ them and says US troops and private contractors (mercenaries) are not authorized to give assistance to private companies. At the same time, however, US military convoys are frequently seen crossing the border into Iraq or passing from Iraq into Syria.

As the Syrian oil is reportedly of poor quality, it may first have to be refined but ultimately, it is ‘batched in’ with oil produced in northern Iraq and piped to Turkey’s southeastern energy hub of Ceyhan. Ninety percent of Iraq’s oil is produced by oilfields in the south but the 10 percent produced in the north generates sufficient revenue to be the subject of acrimonious dispute between the Kurdish regional administration and the government in Baghdad.

Since 1990, a combination of wartime destruction, sabotage and the effects of sanctions has rendered the Kirkuk-Ceyhan pipeline inoperable. Oil from the southern fields had to be shipped out by tanker. While the central government began planning a new pipeline, in 2013 the KRG completed a new dual pipeline running from the Erbil region to Faish al-Khabur, at the junction of the Iraqi-Turkish-Syrian border, and then on to Ceyhan.

In the tangled world of Iraqi oil politics, the central government, while at odds with the KRG over revenue from the northern oilfields, has been using the Kurdish pipeline to ship out some of its own oil.

In Syria, Delta Crescent oversees the production of Syrian oil and reaps some of the benefits; all going to plan, James Cain and James Reese will end up very rich men. The SDF guards the tankers and reaps benefits; the Iraqi Kurds arrange the onward disposition of the oil and take their share, with the Barzanis in particular even further enriched. The passage of the oil to Ceyhan reaps benefits for Turkey as well. Black market profiteers cream off what they can, from sales of contraband oil in Syria.

By keeping Syrian oil out of Syrian hands and keeping Russia (awarded contracts by the Syrian government) out of the oilfield, and by supervising the whole process, the US reaps its share of the benefits, too. The arrangement suits everyone, except of course, the Syrian government and people, to whom the oil belongs.

Jeremy Salt taught at universities in Australia and Turkey, specializing in the modern history of the Middle East. His publications include The Unmaking of the Middle East. A History of Western Disorder in Arab Lands (University of California Press, 2008) and The Last Ottoman Wars. The Human Cost 1877-1923 (University of Utah Press, 2019).

(The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect those of Press TV.)

Until we meet again: A letter to the ‘master of resistance’ Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah

To regain legitimacy, African Union must cut imperialist ties and put Africans first

Trump-Zelensky ‘shouting match’ shows how US props up and discards ‘allies’

Hamas welcomes Gaza reconstruction plan adopted at Arab summit

Columbia University students protest invite to ex-Israeli PM Bennett

VIDEO | Trump lays out divisive agenda in first speech to Congress

FM: Independence a 'conscious choice' for which Iran pays price

VIDEO | Press TV's news headlines

Israel repeatedly breaches terms of Gaza truce, causing significant humanitarian crises

Ayatollah Khamenei donates funds to release needy prisoners

China vows to fight US 'till the end' amid escalating trade war

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website

This makes it easy to access the Press TV website